Exhibit Introduction

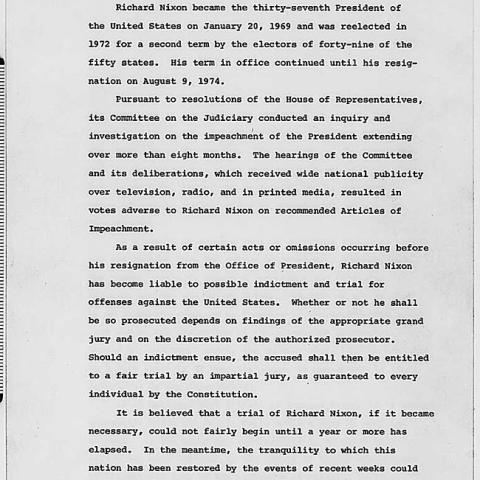

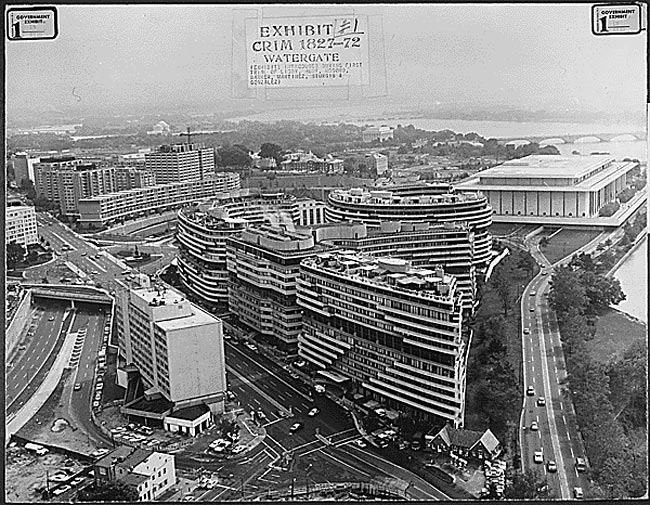

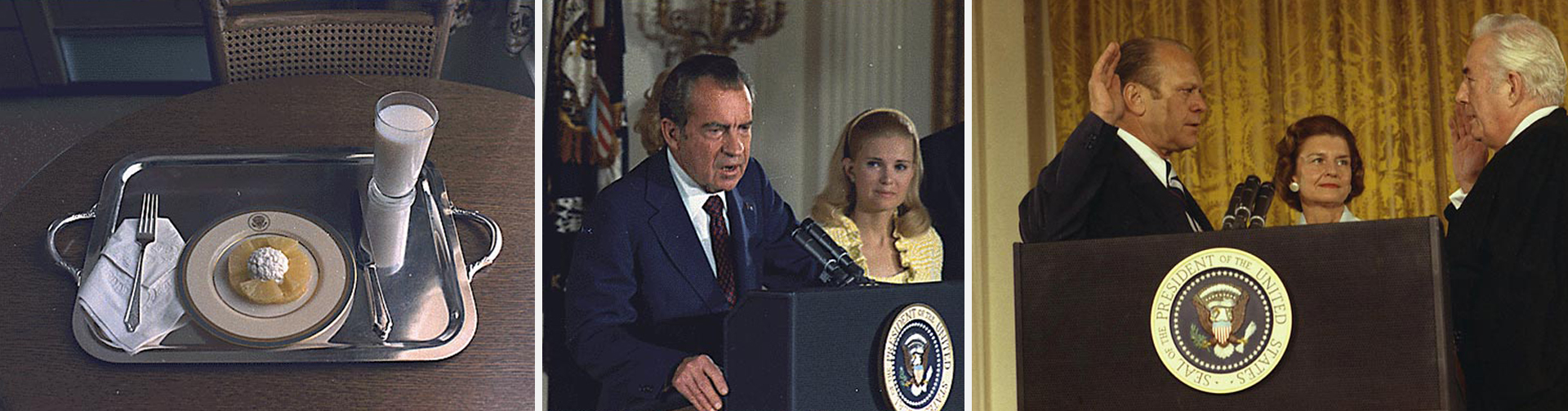

In the early hours of the morning on June 17, 1972, three Washington, DC, police officers responded to a report of a break-in at the Watergate hotel and office complex. They were surprised to find that five burglars, dressed in suits and wearing surgical gloves, had broken into the national headquarters of the Democratic National Committee. The burglars were promptly arrested. The following day, White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler called the break-in a “third-rate burglary.” At a press conference on June 22, President Richard Nixon denied involvement.

For the next twenty-six months, an incredible story of political corruption emerged. Federal investigators and grand juries gathered evidence which gradually connected the Watergate break-in to the Oval Office. Throughout it all, reporters played an essential role keeping the story in the public eye. From the initial burglary trial to Senate hearings to President Nixon’s resignation from office, the public watched as a constitutional crisis unfolded.

The Watergate scandal fundamentally changed how Americans viewed the presidency. Today, “Watergate” is synonymous with political deceit and murky coverups; the suffix “—gate” now applied to political misdeeds both real and perceived. This online exhibit explores this tumultuous time in American history, which culminated with Gerald R. Ford’s ascent to the presidency on August 9, 1974.

The Watergate Trial

Overview

When Judge John Sirica gaveled the trial of the Watergate Seven to order on January 8, 1973, federal investigators had already discovered a covert slush fund used to underwrite nefarious activities against Democrats. The money and the men on trial could be linked to the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP) at whose head sat the former Attorney General of the United States, and President Nixon’s former law partner, John Mitchell. At the trial, E. Howard Hunt, who had planned the break-in, and four of the burglars pleaded guilty. G. Gordon Liddy, who helped in the planning, and James McCord, the other burglar, refused to cooperate, were convicted of various charges, and sentenced to prison.

Shortly after the trial, the United States Senate formed the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, chaired by Senator Sam Ervin (D-NC). Meanwhile, James McCord, contemplating a long prison term, had a change of heart and wrote a letter to Judge Sirica. In it, he claimed that high White House officials had pressured the defendants to plead guilty. The five who pleaded had perjured themselves at the urging of “higher-ups.” With the letter’s release, the saga moved decidedly from being a police story to a political story. It slipped beyond Washington’s beltway and captured national attention.

That January, Time magazine named President Nixon and his national security advisor Henry Kissinger “Men of the Year” for their diplomatic achievements with China. A year later, Time would bestow that honor on Judge Sirica.

People

John Sirica was the son of Italian immigrants who moved from Connecticut to Washington, D. C. in search of a better life. There, young John labored as a trash collector, boxing coach, and acting instructor as he gained a formal education. In 1926 he passed the bar exam, was hired as an attorney in a small law firm, and lost his first thirteen court-appointed felony cases.

Sirica worked with the U. S. Attorney’s office during the Hoover administration. When he married in 1952, his close friend and former boxing champion, Jack Dempsey, served as his best man. Sirica increasingly became active in Republican politics and was appointed to the U. S. District Court for the District of Columbia in 1957. He soon gained the reputation as a maverick judge, at times irritable and careless, and earned the nickname “Maximum John” for his harsh rulings. It was not unusual for his decisions to be overturned during appeal.

In 1973 he presided over the Watergate trials. Quickly growing impatient with their pace and the lack of information yielded, Sirica adopted the controversial tactic of questioning the witnesses himself, and he instructed the jury to consider not only what happened, but also why it happened. Following the trial that saw five of the seven defendants plead guilty and two convicted, Sirica’s suspicions were confirmed, and the Watergate matter was transformed, when one of the burglars, James McCord, wrote a letter to the judge. In it he told how others in court had withheld information and that payments were made by high White House officials to ensure silence. Sirica made the letter public.

Within months, in Senate hearings, the existence of White House tapes was revealed. Sirica ordered the White House to turn over relevant tapes to his court. President Nixon claimed executive privilege, arguing issues of national security shielded the tapes from subpoena. The argument was quickly appealed to the Supreme Court, where the judge, who so often had his rulings overturned, was sustained by the nation’s highest court. The president had to turn over the tapes, and once their contents were revealed, Nixon’s fate was sealed.

Mitchell was born in Detroit, Michigan and earned his law degree from Fordham University. He entered the Navy during World War II and commanded the PT boat unit in which John Kennedy served. Along the way, Mitchell earned two purple hearts and a silver star.

In 1967, Mitchell’s law firm merged with Richard Nixon’s. Mitchell left the new firm in 1968 to manager Nixon’s presidential campaign. Following his victory, Nixon appointed Mitchell to the post of Attorney General. Through the first administration, Mitchell oversaw the Justice Department’s handling of desegregation and affirmative action policies, then resigned in January 1972 to head Nixon’s Committee to Re-elect the President.

It was to Mitchell that Liddy and Magruder brought their ambitious “Gemstone” plan to steal and wring from their opposition political secrets. Mitchell balked at the scope and cost, in the end approving a scaled back, cheaper plan that included breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate hotel. In an effort to distance himself from what he called “the White House horrors,” Mitchell resigned from the CRP in June 1972, but was linked in a Washington Post story in September of that year to a secret campaign fund that underwrote the Watergate caper.

Mitchell was indicted by a federal grand jury in May 1973 and was convicted of conspiracy to obstruct justice, perjury, and obstruction of justice. He served 19 months in federal prison.

Before his association with Nixon’s White House, E. Howard Hunt was a CIA operative who took part in the 1954 coup in Guatemala and the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. Hunt also wrote spy novels, and the character of Jim Phelps in the television series Mission Impossible (played by Peter Graves) was based on him.

As a member of the plumbers, Hunt wrote a memo to Charles Colson in July 1971. Under the heading “Neutralization of Ellsberg,” Hunt proposed collecting “overt, covert, and derogatory information,” the end of which would be to “destroy his [Ellsberg’s] public image and credibility.” This led to the plumbers breaking into the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, Dr. Lewis Fielding.

Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy planned the Watergate break-in. After the burglars were arrested, one was found with Hunt’s name and White House phone number. He was arrested and began making repeated demands for money to Nixon’s personal attorney, John Dean. On March 21, 1973, Dean reported to the president, “The blackmail is continuing…. Hunt now is demanding another $72,000 for his own personal expenses; $50,000 to pay his attorney’s fees – a hundred and twenty some thousand dollars.” Others among the burglars also needed money. “How much money do you need?” the president asked. Dean thought it could be handled with $1,000,000. “We could get that…,” Nixon replied. Hunt’s calls for money and Nixon’s desire to buy his silence were central to the charges of a presidential cover-up. Hunt eventually pleaded guilty to charges of conspiracy, burglary, and wiretapping, and served 33 months in prison.

A former Treasury and FBI agent, Liddy fell in with the group that became known as the Plumbers and took part in the burglary of the office of Dr. Lewis Fielding, Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist. As the 1972 election drew near, Liddy became legal counsel to the CRP and proposed a plan to its management, code-named “Gemstone.” By use of kidnapping, burglary, electronic surveillance, and the use of prostitutes, intelligence could be gleaned on political opponents. John Mitchell, director of CRP, balked at the plan’s extravagance and its high million-dollar price tag and ordered it scaled back.

One part that survived the trimming was a break-in at the DNC headquarters in the Watergate complex. Liddy and E. Howard Hunt oversaw the operation and were arrested along with those who actually broke into the office. Eventually, Liddy stood trial for that offense, for conspiracy in the Fielding case, and for refusing to testify before the Watergate Committee. The courts handed him a stiff fine, and he served about 4 and a half years in prison, the most of any of the conspirators.

Had Sam Ervin never served as the chairman of the Senate Select Committee to Investigate Campaign Practices (i.e., the Watergate Committee), he still would have had a distinguished career. Born in North Carolina, he was a decorated soldier in the First World War, a Harvard Law School graduate, and a successful attorney when in 1954 he won a seat in the Senate. As a freshman Democrat, he was placed on a committee charged with judging whether Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) should be censured for his zealous anti-Communist investigations.

As senator, Ervin established himself as a constitutional expert and a strict constructionist. He alternately sided with liberals defending free speech and separation of church and state, and with conservatives in opposing civil rights legislation and the Equal Rights Amendment. Not until his last year in office, however, did Ervin become a household name, when he was chosen to chair the Watergate Committee. Sitting before the cameras, he became something of a television icon, though he never embraced the pop culture that warmed to him. In an article reporting his death in 1985, the Washington Post wrote, “At a time when Americans were buffeted by the Vietnam War and Watergate and increasingly distrustful of their leaders, Ervin came across as a stern father figure who wasn’t confused about what was right and wrong, moral and evil, and who took for granted the moral courage to stand up for what was right.”

Ervin’s civic rectitude was particularly offended when President Nixon refused to allow his aides to testify before his committee, shielding them behind his claim of executive privilege. “Divine Right of kings went out with the American Revolution and doesn’t belong to White House aides,” Ervin chided. “I don’t think we have any such thing as royalty or nobility that exempts them…. That is not executive privilege. That is executive poppycock!” Turning his attention to Nixon himself, Ervin recalled a quip from Mark Twain. “The truth is very precious; use it sparingly.” Nixon, Ervin concluded, “…used it sparingly.”

Richard Nixon was a hardened veteran of the political arena. He had represented California in the House and Senate, where he earned a reputation as a fierce anti-Communist and a bare-knuckles campaigner. As Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president, Nixon had stayed on the ticket in 1952 only by countering charges of benefiting from a political slush fund through a last-minute televised appeal to the American public. After Ike’s two terms, Nixon secured the nomination in 1960, but lost by a razor-thin margin to his congressional classmate of 1946, John Kennedy. In 1962, Nixon ran for governor of California and again was defeated. But he recognized a political vacuum following Barry Goldwater’s landslide loss to Lyndon Johnson in 1964. His dogged foreign travels and nation-wide campaigning for Republican candidates in the 1966 mid-term election paid dividends two years later when the Republican party crowned his remarkable comeback by once again making him their presidential nominee.

In the national tumult that marred the year 1968, Nixon withstood the challenge of Vice President Hubert Humphrey who was saddled to an administration held responsible for an unpopular war and domestic unrest, and a strong third-party challenge by Alabama Governor George Wallace, who capitalized on racial discord. Nixon won the election with 43 percent of the popular vote (56 percent of the electoral vote). Two close presidential races intensified lessons Nixon drew from the rough and tumble of other political experiences. As he planned for re-election in 1972, he determined to leave nothing to chance. The campaign would be played by hardball rules, and Nixon would use every advantage the incumbency afforded him.

Conventional wisdom held that the Democrats would field a strong challenger in 1972. But by the end of the primaries, Ted Kennedy, Hubert Humphrey, and Edmund Muskie were gone, leaving the dark-horse Senator from South Dakota, George McGovern. The war in Vietnam dominated the campaign. As McGovern called for immediate withdrawal of U. S. troops and sharp reductions in defense spending, Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, sought to calm public unrest over the war by claiming that peace was near.

Yet even as he was driving toward an easy victory, Nixon was anything but calm. In response to the leaking of sensitive military information, Nixon had formed a special investigations unit called the “Plumbers” to plug those leaks. Not trusting his campaign to the normal Republican election framework, Nixon established the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP), headed by his former law partner and attorney general, John Mitchell. Through it the campaign was orchestrated, but a clandestine campaign was also waged. The Plumbers and others were used to raise large amounts of money, gather intelligence for political purposes, and spear the opposition.

Nixon crushed McGovern that November, winning 61 percent of the popular vote and all but 17 votes in the Electoral College. His overwhelming victory did not carry over to Capitol Hill, however, where his party lost seats in the Senate and enjoyed only modest gains in the House. In both chambers, the Republicans remained in the minority, a status that would prove costly as Nixon attempted to control the Watergate investigation in his second term. His greatest political victory was muted by this “third-rate burglary.” Though buoyed by the triumph, within six months of his January 1973 inauguration, the investigation that had been focused primarily on his campaign staff would be knocking on the door of his Oval Office, demanding he turn over until-then secret tape recordings. Once surrendered, his complicity in the crimes of his administration was revealed, and his presidency was doomed.

To help him break into Democratic National Headquarters at the Watergate Hotel, E. Howard Hunt enlisted the help of four Cubans from Miami’s anti-Castro community. Bernard L. Barker was a real estate agent who had worked with Hunt at the CIA. Eugenio Martinez and Frank A. Sturgis were associates of Barker, each with CIA ties. The fourth Cuban, Virgilio R. Gonzales, was a locksmith. The final burglar, James W. McCord, helped organize security for the CRP. He, too, was a former CIA agent and had worked with the FBI.

Assisted by Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy, the five operatives entered the DNC headquarters on Memorial Day weekend 1972, photographing files and bugging telephones. Later, the result of their work was shown to John Mitchell. He was unsatisfied, and the burglars returned to the Watergate in the early hours of June 17. While they were taking more photographs and replacing faulty bugs, Watergate security guard Frank Wills discovered tape blocking the bolt of a door that should have been locked. He called police, who arrived and arrested the burglars while still in the DNC’s office. Hunt and Liddy were arrested later. Cash, false identification, and other information found on the men linked them to Nixon’s re-election committee.

Documents

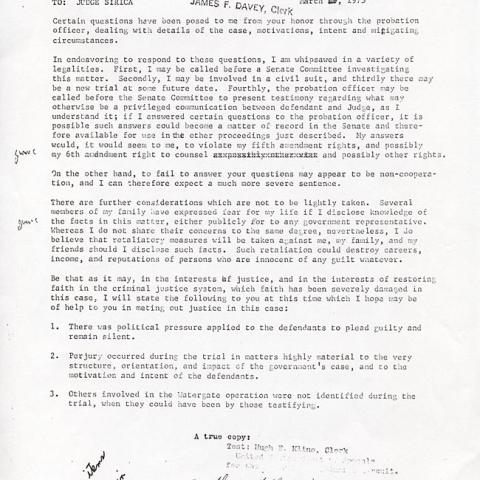

Transcript of Letter from James W. McCord, Jr., to Judge John Sirica

James W. McCord, Jr.

7 Winder Court

Rockville , Maryland 20850

TO: JUDGE SIRICA March 19, 1973

Certain questions have been posed to me from your honor through the probation officer, dealing with details of the case, motivations, intent and mitigating circumstances.

In endeavoring to respond to these questions, I am whipsawed in a variety of legalities. First, I may be called before a Senate Committee investigating this matter. Secondly, I may be involved in a civil suit, and thirdly there may be a new trial at some future date. Fourthly, the probation officer may be called before the Senate Committee to present testimony regarding what may otherwise be a privileged communication between defendant and Judge, as I understand it; if I answered certain questions to the probation officer, it is possible such answers could become a matter of record in the Senate and there-fore available for use in the other proceedings just described. My answers would, it would seem to me, to violate my fifth amendment rights, and possibly my 6 th amendment right to counsel and possibly other rights.

On the other hand, to fail to answer your questions may appear to be non-cooperation, and I can therefore expect a much more severe sentence.

There are further considerations which are not to be lightly taken. Several members of my family have expressed fear for my life if I disclose knowledge of the facts in this matter, either publicly or to any government representative. Whereas I do not share their concerns to the same degree, nevertheless, I do believe that retaliatory measures will be taken against me, my family, and my friends should I disclose such facts. Such retaliation could destroy careers, income, and reputations of persons who are innocent of any guilt whatever.

Be that as it may, in the interests of justice, and in the interests of restoring faith in the criminal justice system, which faith has been severely damaged in this case, I will state the following to you at this time which I hope may be of help to you in meting out justice in this case:

- There was political pressure applied to the defendants to plead guilty and remain silent.

- Perjury occurred during the trial in matters highly material to the very structure, orientation, and impact of the government's case, and to the motivation and intent of the defendants.

- Others involved in the Watergate operation were not identified during the trial, when they could have been by those testifying.

- The Watergate operation was not a CIA operation. The Cubans may have been misled by others into believing that it was a CIA operation. I know for a fact that it was not.

- Some statements were unfortunately made by a witness which left the Court with the impression that he was stating untruths, or withholding facts of his knowledge, when in fact only honest errors of memory were involved.

- My motivations were different than those of the others involved, but were not limited to, or simply those offered in my defense during the trial. This is no fault of my attorneys, but of the circumstances under which we had to prepare my defense.

Following sentence, I would appreciate the opportunity to talk with you privately in chambers. Since I cannot feel confident in talking with an FBI agent, in testifying before a Grand Jury whose U.S. Attorneys work for the Department of Justice, or in talking with other government representatives, such a discussion with you would be of assistance to me.

I have not discussed the above with my attorneys as a matter of protection for them.

I give this statement freely and voluntarily, fully realizing that I may be prosecuted for giving a false statement to a Judicial Official, if the statements herein are knowingly untrue. The statements are true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief.

[signed]

James W. McCord, Jr.

Timeline

Senate Hearing

Overview

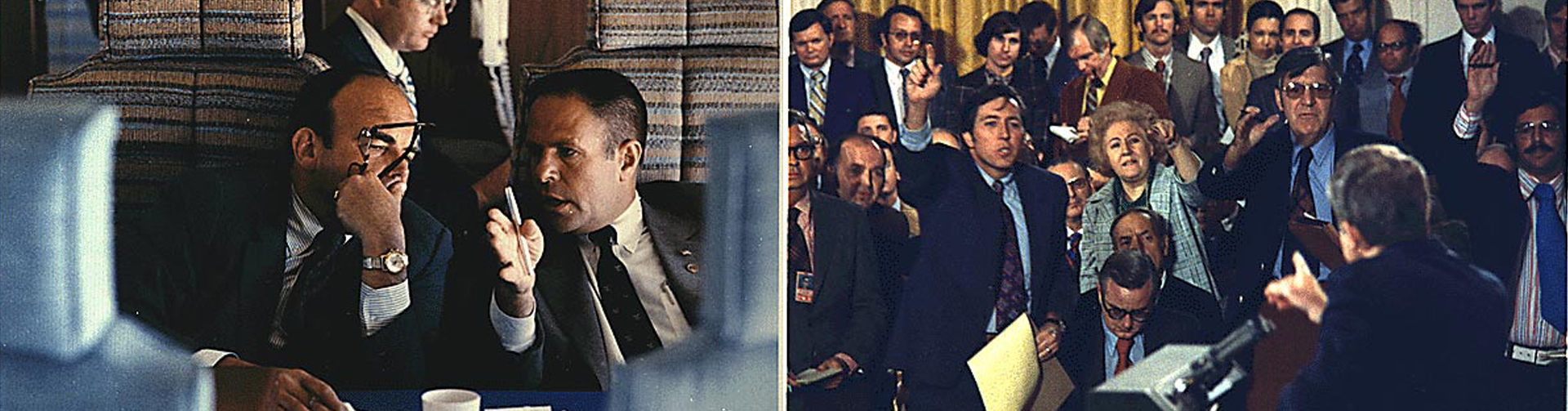

The seriousness of the Watergate matter was measured by the strength of the Senate’s vote to create an investigative committee – 77 to 0. By the time it began its televised hearings in mid-May 1973, its chairman, the affable, homespun, Senator Ervin and his team of investigators were flanking the White House defense. James McCord was cooperating, and White House counsel to the president, John Dean, was a veritable fountain of allegations. President Nixon had fired Dean on April 30. That same day Nixon’s chief of staff Bob Haldeman and Domestic Counsel John Ehrlichman had resigned because of their role in Watergate. And Attorney General Richard Kleindienst resigned stating he was incapable of prosecuting close friends.

In an attempt to mitigate the damage, Nixon named Elliot Richardson Attorney General. Following Nixon’s instructions, Richardson announced on May 18, that the Justice Department was appointing its own special prosecutor, former Solicitor General Archibald Cox, to investigate possible administration misdeeds.

Meanwhile, the White House announced that the president had no prior knowledge of the Watergate matter. Yet Dean’s testimony refuted that claim. He told a stunned Senate committee and, through the gathered media, an astonished public, that Nixon not only knew of the break-in, the president had directed in the cover-up. But how could such claims be corroborated?

The answer came on July 16, when Alexander Butterfield, a former White House appointments secretary, quietly and unexpectedly informed the Senate committee that a system of taping conversations and telephone calls was in place within the White House.

People

Had Sam Ervin never served as the chairman of the Senate Select Committee to Investigate Campaign Practices (i.e., the Watergate Committee), he still would have had a distinguished career. Born in North Carolina, he was a decorated soldier in the First World War, a Harvard Law School graduate, and a successful attorney when in 1954 he won a seat in the Senate. As a freshman Democrat, he was placed on a committee charged with judging whether Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) should be censured for his zealous anti-Communist investigations.

As senator, Ervin established himself as a constitutional expert and a strict constructionist. He alternately sided with liberals defending free speech and separation of church and state, and with conservatives in opposing civil rights legislation and the Equal Rights Amendment. Not until his last year in office, however, did Ervin become a household name, when he was chosen to chair the Watergate Committee. Sitting before the cameras, he became something of a television icon, though he never embraced the pop culture that warmed to him. In an article reporting his death in 1985, the Washington Post wrote, “At a time when Americans were buffeted by the Vietnam War and Watergate and increasingly distrustful of their leaders, Ervin came across as a stern father figure who wasn’t confused about what was right and wrong, moral and evil, and who took for granted the moral courage to stand up for what was right.”

Ervin’s civic rectitude was particularly offended when President Nixon refused to allow his aides to testify before his committee, shielding them behind his claim of executive privilege. “Divine Right of kings went out with the American Revolution and doesn’t belong to White House aides,” Ervin chided. “I don’t think we have any such thing as royalty or nobility that exempts them…. That is not executive privilege. That is executive poppycock!” Turning his attention to Nixon himself, Ervin recalled a quip from Mark Twain. “The truth is very precious; use it sparingly.” Nixon, Ervin concluded, “…used it sparingly.”

On June 30, 1971, President Nixon quizzed his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, about people who could be trusted to run covert political operations. Only weeks earlier Nixon had felt the sting of seeing portions of classified documents regarding the Vietnam War published in the New York Times. “…Dean can and his group,” Haldeman replied. “Well, do they understand how we want to play the game or can you tell them,” Nixon asked. “Uh-huh,” Haldeman answered. “Do they know how tough it has to be played?” Nixon drove home a key point. “Yes,” said Haldeman. “Dean, you say…,” a brooding president pondered the name.

Dean came to the White House as a presidential aide and eventually became Nixon’s legal counsel. In between, Dean was deeply involved in Watergate. Prior to the 1972 election he had discussed with John Mitchell the need to gather political intelligence. As Watergate broke, Haldeman and John Ehrlichman trusted their bright attorney to control the political fall out after the burglars were arrested, part of which involved him paying them large sums of money. The president lauded his efforts. “…Dean is a pretty good gem,” Nixon confided to Haldeman on March 2, 1973. “He’s a real cool cookie, isn’t he,” Haldeman agreed. “I don’t know about cool,” the president added, “but he is awfully smart.” That same month, however, things were to unravel quickly. And soon Nixon’s enthusiasm toward his “smart gem” cooled measurably.

To help him grasp the events surrounding Watergate, Nixon repeatedly asked Dean to write an account, eventually sending him to Camp David in early April to get it done. Dean, however, was beginning to feel increasingly uncomfortable. James McCord’s March 19, letter to Judge Sirica, asserting that “political pressure” had squeezed guilty pleas and silence from the Watergate defendants, unnerved him. As recently as March 21, Dean met with the president to warn him of the metastasizing problem of the cover-up, telling Nixon of “a cancer … close to the presidency” and of the increasing demands by the burglars for money. Additionally, Nixon’s nominee to head the FBI, L. Patrick Gray, told a Senate committee he had given FBI files on Watergate to Dean.

In the face of this heat, Dean’s resolve wilted. Instead of handing the president a written account of Watergate, he hired a personal attorney. Fearing the White House was making him the fall guy, Dean began cooperating with federal investigators. Accordingly, Nixon fired Dean on April 30. Under cover of limited immunity, Dean testified before the Senate Watergate committee in late June, claiming the president was involved in the cover-up, that Nixon knew about hush money paid to the burglars, and that Ehrlichman ordered evidence be destroyed. Further, Dean claimed, Nixon had known about the break-in as early as September 15, 1972, six months earlier than the president had previously admitted.

Eventually, investigators learned of Nixon’s secret tapes. Their recordings sufficiently corroborated the testimony of Dean and others (while refuting assertions offered by administration witnesses), and Nixon was forced to resign. As for Dean, he was charged with obstruction of justice and spent four months in prison.

An Eagle Scout, Navy veteran of World War II, and advertising executive, H. R. Haldeman had long admired Richard Nixon. It was during Congressman Nixon’s fight to expose Alger Hiss and his ties with Communism that Haldeman first took notice of his fellow Californian. In 1952, Haldeman’s father was one of the contributors to Nixon’s private campaign fund that almost derailed his spot as Eisenhower’s running mate. The younger Haldeman worked as an advance man in Nixon’s campaigns in 1956 and 1960 and managed his failed race for governor of California in 1962.

By 1968, Haldeman had earned Nixon’s confidence and loyalty. The president-elect appointed him chief of staff. Playing to Nixon’s reclusive management style, Haldeman became the “gatekeeper,” describing himself as the president’s “SOB.” Haldeman was a key player at many of the critical moments during the Watergate crisis. The June 20, 1972 tape containing the mysterious 18 ½ minute gap was a conversation between Haldeman and Nixon. The “smoking gun” tape, uncovered after the Supreme Court ordered Nixon to turn over relevant tapes, contained a conversation between the two plotting to instruct the CIA to tell the FBI to steer clear of investigating the Watergate break-in for reasons of national security.

Finally, after White House counsel John Dean implicated Haldeman and others in testimony before the Senate Watergate committee, he and Nixon’s domestic policy counsel, John Ehrlichman, resigned on April 30, 1973. With Haldeman’s resignation, the president lost more than his bulldog, more than his closest advisor. Following his speech to the nation in which he announced Haldeman’s dismissal, Haldeman called Nixon. Immediately, the president said, “I hope I didn’t let you down.” “No, sir,” replied Haldeman. The conversation, thick with emotion, stumbled on. “I don’t know whether you can call and get any reactions and call me back – like the old style. Would you mind?” Nixon asked. “I don’t think I can. I don’t –,” Haldeman began to answer. Nixon interrupted, “No, I agree.” The call continued for a few awkward moments, then Nixon, sensing it was spent, said for the third time, “I love you, as you know.” “Okay,” Haldeman said. “Like my brother,” Nixon added. In his memoirs, Nixon recalled, “from that day on the presidency lost all joy for me.”

Haldeman served eighteen months in prison for his Watergate-related crimes.

John Erhlichman was President Nixon’s top domestic affairs advisor. Together with Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, the two sought to protect the reclusive president, forming around him what others referred to as a “Berlin Wall.” Indeed, it was Ehrlichman and Haldeman who, in an effort to stop military information from leaking to the media, instructed Ehrlichman’s chief assistant, Egil Krogh, to oversee the “plumbers,” a secret group that undertook covert political operations. After Daniel Ellsberg secreted the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times, Ehrlichman instructed the plumbers to raid the California office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in search of incriminating evidence. Reporting on those efforts, Erhlichman tried not to reveal too much to the president. “We had one little operation. It’s been aborted out in Los Angeles which, I think, is better that you don’t know about,” he informed the president in September 1971.

After the Watergate investigation began, Nixon’s nominee for Director of the FBI, L. Patrick Gray, absorbed many of Congress’ blows during confirmation hearings. Subjected to heated criticism, especially over his relationship with the president’s legal counsel, John Dean, prospects for his approval looked bleak. Ehrlichman calculated political value in Congress eviscerating Gray’s nomination. It shifted the focus of Watergate from the White House. As Ehrlichman advised the president, better Gray be left “twisting, slowly, slowly in the wind.”

In April 1973, alienated from the White House by Nixon’s devotion to Haldeman and Ehrlichman and his own decision to freely testify before the grand jury and Senate committee, Dean implicated the president and his two advisors in the Watergate cover-up. On April 30, Nixon fired Dean and, following wrenching, emotional meetings with Ehrlichman and Haldeman, Nixon reluctantly accepted their resignations, along with the resignation of his Attorney General, Richard Kleindienst. Later convicted of conspiracy, obstruction of justice, making false statements, and other charges, Ehrlichman served eighteen months in federal prison.

After being turned down by his eight previous choices, Attorney General Elliot Richardson offered his former Harvard Law School professor, Archibald Cox, the position of Watergate Special Prosecutor. Assured he could act independently, with White House cooperation, and be dismissed only for extraordinary improprieties, Cox accepted.

Less than two months following his appointment in May 1973, Cox learned with the rest of America of Nixon’s secret tapes. Over the next few months, Cox, the Senate Watergate committee, and Judge John Sirica battled with the White House over those tapes. During that fight, after Sirica ordered Nixon to comply with the committee and Cox’s demand, Cox offered the president a compromise. The White House could prepare transcripts of the subpoenaed tapes, omitting sections it deemed outside the interest of the investigators. A third party would review the tapes and the transcripts. Once in agreement with the White House, this arbiter would deliver the transcripts to Cox and the grand jury. Nixon refused the offer, but his hand was forced when a federal court upheld Judge Sirica’s order.

Weakened by the decision, Nixon offered Cox his own compromise. The White House would prepare transcripts, and a man of Nixon’s choosing would confirm their legitimacy. In exchange, Cox would agree to call for no more evidence. Nixon was distrustful of Cox and his many Democratic ties, especially to the Kennedys. Cox had served as an advisor to Congressman John Kennedy and as his solicitor general during Kennedy’s presidency. But sterner stuff than partisanship animated Cox, whose family tree was anchored by Roger Sherman, the “Mount Atlas” of the Founding Fathers. Indeed, Cox’s childhood was rich with stories of his great grandfather, William Maxwell Evarts, whose impassioned defense of Andrew Johnson in 1868 saved the impeached president in his Senate trial. Cox rejected Nixon’s overture on Saturday, October 20.

That day, Nixon fired the special prosecutor and, in so doing, lost his attorney general and assistant attorney general, both of whom resigned in protest. Cox issued a terse, one-sentence response when he learned of his dismissal. Picking up on a phrase made famous by John Adams, he said, “Whether ours shall continue to be a government of laws and not of men is now before Congress and ultimately the American people.” The following Monday, outraged members of Congress introduced twenty-two separate resolutions calling for Nixon’s impeachment, testing Cox’s contention.

Richard Nixon was a hardened veteran of the political arena. He had represented California in the House and Senate, where he earned a reputation as a fierce anti-Communist and a bare-knuckles campaigner. As Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president, Nixon had stayed on the ticket in 1952 only by countering charges of benefiting from a political slush fund through a last-minute televised appeal to the American public. After Ike’s two terms, Nixon secured the nomination in 1960, but lost by a razor-thin margin to his congressional classmate of 1946, John Kennedy. In 1962, Nixon ran for governor of California and again was defeated. But he recognized a political vacuum following Barry Goldwater’s landslide loss to Lyndon Johnson in 1964. His dogged foreign travels and nation-wide campaigning for Republican candidates in the 1966 mid-term election paid dividends two years later when the Republican party crowned his remarkable comeback by once again making him their presidential nominee.

In the national tumult that marred the year 1968, Nixon withstood the challenge of Vice President Hubert Humphrey who was saddled to an administration held responsible for an unpopular war and domestic unrest, and a strong third-party challenge by Alabama Governor George Wallace, who capitalized on racial discord. Nixon won the election with 43 percent of the popular vote (56 percent of the electoral vote). Two close presidential races intensified lessons Nixon drew from the rough and tumble of other political experiences. As he planned for re-election in 1972, he determined to leave nothing to chance. The campaign would be played by hardball rules, and Nixon would use every advantage the incumbency afforded him.

Conventional wisdom held that the Democrats would field a strong challenger in 1972. But by the end of the primaries, Ted Kennedy, Hubert Humphrey, and Edmund Muskie were gone, leaving the dark-horse Senator from South Dakota, George McGovern. The war in Vietnam dominated the campaign. As McGovern called for immediate withdrawal of U. S. troops and sharp reductions in defense spending, Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, sought to calm public unrest over the war by claiming that peace was near.

Yet even as he was driving toward an easy victory, Nixon was anything but calm. In response to the leaking of sensitive military information, Nixon had formed a special investigations unit called the “Plumbers” to plug those leaks. Not trusting his campaign to the normal Republican election framework, Nixon established the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP), headed by his former law partner and attorney general, John Mitchell. Through it the campaign was orchestrated, but a clandestine campaign was also waged. The Plumbers and others were used to raise large amounts of money, gather intelligence for political purposes, and spear the opposition.

Nixon crushed McGovern that November, winning 61 percent of the popular vote and all but 17 votes in the Electoral College. His overwhelming victory did not carry over to Capitol Hill, however, where his party lost seats in the Senate and enjoyed only modest gains in the House. In both chambers, the Republicans remained in the minority, a status that would prove costly as Nixon attempted to control the Watergate investigation in his second term. His greatest political victory was muted by this “third-rate burglary.” Though buoyed by the triumph, within six months of his January 1973 inauguration, the investigation that had been focused primarily on his campaign staff would be knocking on the door of his Oval Office, demanding he turn over until-then secret tape recordings. Once surrendered, his complicity in the crimes of his administration was revealed, and his presidency was doomed.

Documents

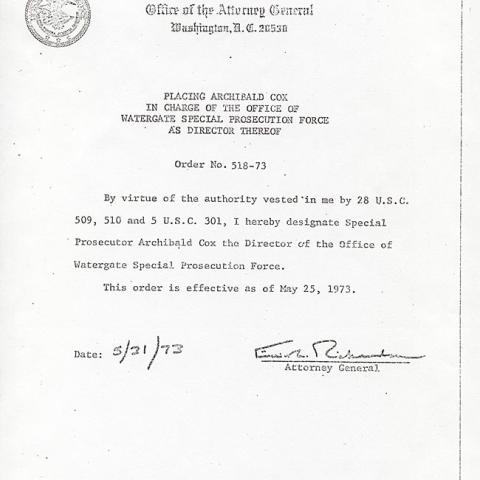

Transcript of Department of Justice Order No. 518-73

Office of the Attorney General

Washington , D.C. 20530

PLACING ARCHIBALD COX

IN CHARGE OF THE OFFICE OF

WATERGATE SPECIAL PROSECUTION FORCE

AS DIRECTOR THEREOF

Order No. 518-73

By virtue of the authority vested in me by 28 U.S.C. 509, 510 and 5 U.S.C. 301, I hereby designate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox the Director of the Office of Watergate Special Prosecution Force.

This order is effective as of May 25, 1973.

Date: 5/31/73

Elliot Richardson [signed]

Attorney General

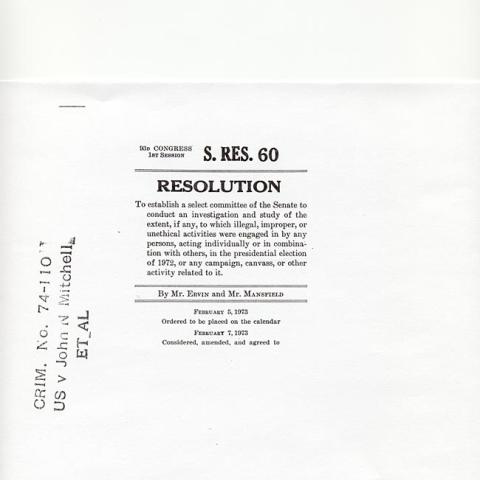

Transcript of Government Exhibit 61 in United States v. Mitchell, et al.

93D CONGRESS

1ST SESSION

S. RES. 60

RESOLUTION

To establish a select committee of the Senate to conduct an investigation and study of the extent, if any, to which illegal, improper, or unethical activities were engaged in by any persons, acting individually or in combination with others, in the presidential election of 1972, or any campaign, canvass, or other activity related to it.

By Mr. ERVIN and Mr. MANSFIELD

FEBRUARY 5, 1973

Ordered to be placed on the calendar

FEBRUARY 7, 1973

Considered, amended, and agreed to

Timeline

Battle for the Tapes

Overview

Less than a week following Butterfield’s revelation, Nixon ordered an end to White House taping. Shortly afterward, the Senate committee, Special Prosecutor Cox, and Judge Sirica ordered relevant tapes be turned over. Nixon refused, claiming executive privilege. By August the matter was in court. Nixon addressed the nation on August 15, 1973, explaining to the people why confidential conversations between the president and his advisors should not be made a matter of public record. Lawyers for the Watergate committee and Special Prosecutor’s office argued that conversations dealing with matters of potential illegality should not be suppressed by claims of executive privilege.

On October 12, Nixon nominated Congressman Gerald Ford (R-MI) to fill the vacancy left by the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew following charges of bribery and tax evasion. That same day, the U. S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Washington ruled that Nixon must turn over the tapes to Judge Sirica. Knowing the implications and rather than comply, Nixon suggested a compromise, offering edited transcripts to the various investigating offices. Special Prosecutor Cox refused, and on the evening of October 20, a political bloodletting labeled the “Saturday Night Massacre” ensued. Nixon, angered by Cox’s response, ordered Attorney General Richardson to fire the prosecutor. Richardson resigned rather than obey. Immediately afterward, Nixon ordered Richardson’s assistant, William Ruckelshaus, to fire Cox. He, too, refused and resigned. Finally, Solicitor General Robert Bork was given the order and carried it out.

A hail of criticism pelted the White House, including calls for Nixon’s impeachment. In the face of this outrage, Nixon relented and agreed to surrender the subpoenaed tapes. He then appointed Texas attorney Leon Jaworski to replace Cox.

Troubling revelations followed the release of the tapes. The White House claimed that some tapes subject to the subpoena did not exist. One contained an erased gap that stretched for over eighteen minutes. Nixon’s secretary, Rose Mary Woods, and others in the White House offered conflicting accounts for what experts contended were five or more separate erasures. White House Chief of Staff Alexander Haig credited the gap to “some sinister force.” Others outside the White House concluded key evidence had been deliberately destroyed.

People

Richard Nixon was a hardened veteran of the political arena. He had represented California in the House and Senate, where he earned a reputation as a fierce anti-Communist and a bare-knuckles campaigner. As Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president, Nixon had stayed on the ticket in 1952 only by countering charges of benefiting from a political slush fund through a last-minute televised appeal to the American public. After Ike’s two terms, Nixon secured the nomination in 1960, but lost by a razor-thin margin to his congressional classmate of 1946, John Kennedy. In 1962, Nixon ran for governor of California and again was defeated. But he recognized a political vacuum following Barry Goldwater’s landslide loss to Lyndon Johnson in 1964. His dogged foreign travels and nation-wide campaigning for Republican candidates in the 1966 mid-term election paid dividends two years later when the Republican party crowned his remarkable comeback by once again making him their presidential nominee.

In the national tumult that marred the year 1968, Nixon withstood the challenge of Vice President Hubert Humphrey who was saddled to an administration held responsible for an unpopular war and domestic unrest, and a strong third-party challenge by Alabama Governor George Wallace, who capitalized on racial discord. Nixon won the election with 43 percent of the popular vote (56 percent of the electoral vote). Two close presidential races intensified lessons Nixon drew from the rough and tumble of other political experiences. As he planned for re-election in 1972, he determined to leave nothing to chance. The campaign would be played by hardball rules, and Nixon would use every advantage the incumbency afforded him.

Conventional wisdom held that the Democrats would field a strong challenger in 1972. But by the end of the primaries, Ted Kennedy, Hubert Humphrey, and Edmund Muskie were gone, leaving the dark-horse Senator from South Dakota, George McGovern. The war in Vietnam dominated the campaign. As McGovern called for immediate withdrawal of U. S. troops and sharp reductions in defense spending, Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, sought to calm public unrest over the war by claiming that peace was near.

Yet even as he was driving toward an easy victory, Nixon was anything but calm. In response to the leaking of sensitive military information, Nixon had formed a special investigations unit called the “Plumbers” to plug those leaks. Not trusting his campaign to the normal Republican election framework, Nixon established the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP), headed by his former law partner and attorney general, John Mitchell. Through it the campaign was orchestrated, but a clandestine campaign was also waged. The Plumbers and others were used to raise large amounts of money, gather intelligence for political purposes, and spear the opposition.

Nixon crushed McGovern that November, winning 61 percent of the popular vote and all but 17 votes in the Electoral College. His overwhelming victory did not carry over to Capitol Hill, however, where his party lost seats in the Senate and enjoyed only modest gains in the House. In both chambers, the Republicans remained in the minority, a status that would prove costly as Nixon attempted to control the Watergate investigation in his second term. His greatest political victory was muted by this “third-rate burglary.” Though buoyed by the triumph, within six months of his January 1973 inauguration, the investigation that had been focused primarily on his campaign staff would be knocking on the door of his Oval Office, demanding he turn over until-then secret tape recordings. Once surrendered, his complicity in the crimes of his administration was revealed, and his presidency was doomed.

After being turned down by his eight previous choices, Attorney General Elliot Richardson offered his former Harvard Law School professor, Archibald Cox, the position of Watergate Special Prosecutor. Assured he could act independently, with White House cooperation, and be dismissed only for extraordinary improprieties, Cox accepted.

Less than two months following his appointment in May 1973, Cox learned with the rest of America of Nixon’s secret tapes. Over the next few months, Cox, the Senate Watergate committee, and Judge John Sirica battled with the White House over those tapes. During that fight, after Sirica ordered Nixon to comply with the committee and Cox’s demand, Cox offered the president a compromise. The White House could prepare transcripts of the subpoenaed tapes, omitting sections it deemed outside the interest of the investigators. A third party would review the tapes and the transcripts. Once in agreement with the White House, this arbiter would deliver the transcripts to Cox and the grand jury. Nixon refused the offer, but his hand was forced when a federal court upheld Judge Sirica’s order.

Weakened by the decision, Nixon offered Cox his own compromise. The White House would prepare transcripts, and a man of Nixon’s choosing would confirm their legitimacy. In exchange, Cox would agree to call for no more evidence. Nixon was distrustful of Cox and his many Democratic ties, especially to the Kennedys. Cox had served as an advisor to Congressman John Kennedy and as his solicitor general during Kennedy’s presidency. But sterner stuff than partisanship animated Cox, whose family tree was anchored by Roger Sherman, the “Mount Atlas” of the Founding Fathers. Indeed, Cox’s childhood was rich with stories of his great grandfather, William Maxwell Evarts, whose impassioned defense of Andrew Johnson in 1868 saved the impeached president in his Senate trial. Cox rejected Nixon’s overture on Saturday, October 20.

That day, Nixon fired the special prosecutor and, in so doing, lost his attorney general and assistant attorney general, both of whom resigned in protest. Cox issued a terse, one-sentence response when he learned of his dismissal. Picking up on a phrase made famous by John Adams, he said, “Whether ours shall continue to be a government of laws and not of men is now before Congress and ultimately the American people.” The following Monday, outraged members of Congress introduced twenty-two separate resolutions calling for Nixon’s impeachment, testing Cox’s contention.

John Sirica was the son of Italian immigrants who moved from Connecticut to Washington, D. C. in search of a better life. There, young John labored as a trash collector, boxing coach, and acting instructor as he gained a formal education. In 1926 he passed the bar exam, was hired as an attorney in a small law firm, and lost his first thirteen court-appointed felony cases.

Sirica worked with the U. S. Attorney’s office during the Hoover administration. When he married in 1952, his close friend and former boxing champion, Jack Dempsey, served as his best man. Sirica increasingly became active in Republican politics and was appointed to the U. S. District Court for the District of Columbia in 1957. He soon gained the reputation as a maverick judge, at times irritable and careless, and earned the nickname “Maximum John” for his harsh rulings. It was not unusual for his decisions to be overturned during appeal.

In 1973 he presided over the Watergate trials. Quickly growing impatient with their pace and the lack of information yielded, Sirica adopted the controversial tactic of questioning the witnesses himself, and he instructed the jury to consider not only what happened, but also why it happened. Following the trial that saw five of the seven defendants plead guilty and two convicted, Sirica’s suspicions were confirmed, and the Watergate matter was transformed, when one of the burglars, James McCord, wrote a letter to the judge. In it he told how others in court had withheld information and that payments were made by high White House officials to ensure silence. Sirica made the letter public.

Within months, in Senate hearings, the existence of White House tapes was revealed. Sirica ordered the White House to turn over relevant tapes to his court. President Nixon claimed executive privilege, arguing issues of national security shielded the tapes from subpoena. The argument was quickly appealed to the Supreme Court, where the judge, who so often had his rulings overturned, was sustained by the nation’s highest court. The president had to turn over the tapes, and once their contents were revealed, Nixon’s fate was sealed.

Gerald R. Ford had served in Congress since 1949. As leader of the Republican minority in the U.S. House of Representatives, he had a keen sense of the political; the son of hard working, loving parents, he knew right from wrong. Two days after the Watergate break-in he confided to a friend, “Nixon ought to get to the bottom of this and get rid of anybody who’s involved in it.” That same afternoon, he asked Nixon’s campaign manager, John Mitchell, whether anyone at the White House was implicated. “Absolutely not,” Mitchell assured him.

Fourteen months later, after being warned by White House Counsellor Melvin Laird that things were about to get worse, Ford learned that Vice President Spiro Agnew was under investigation for accepting kickbacks from Maryland contractors. By October Agnew had resigned, and Nixon faced the task of appointing a new Vice President in the midst of his court battle over the White House tapes. He needed someone prepared to be President, in agreement with his policies, and who could be confirmed by a Congress made increasingly skeptical by Watergate revelations. Nixon chose Ford, a friend and ally, who enjoyed enormous respect among his peers.

On December 6, 1973, in the House chamber, Ford took the oath of office and became Vice President. Immediately he set about promoting the President’s agenda, attempting to heal the rifts between Congress and the White House, but also defending the President, who he believed had made mistakes but had committed no impeachable offenses.

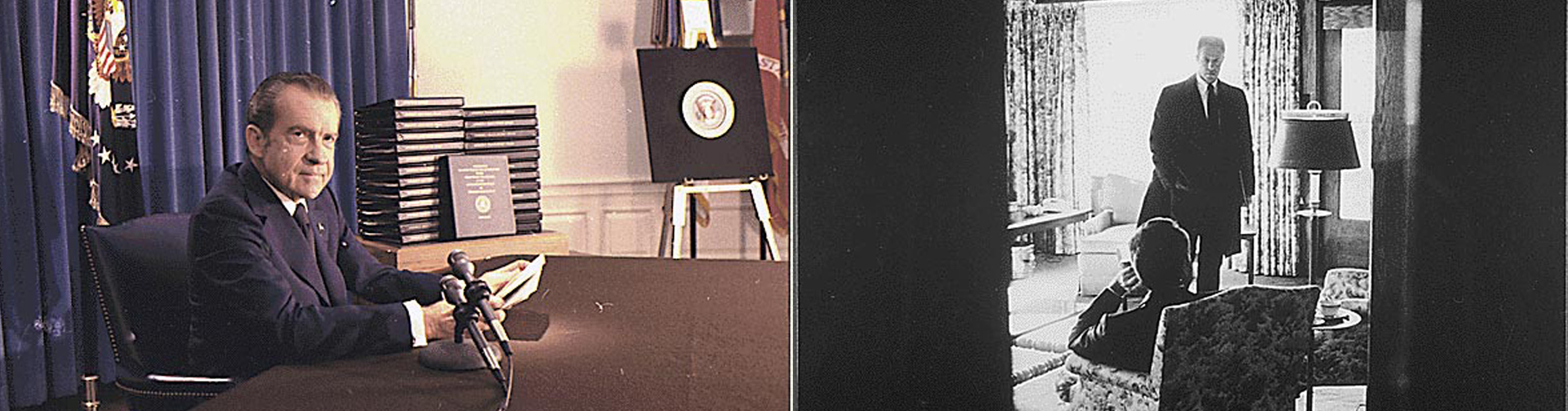

Ford’s defense of Nixon continued until August 6, 1974. A few days earlier he had been warned by Nixon’s chief of staff, Alexander Haig, that information about to be released would undermine the President’s position – that he had known about the break-in much earlier than previously disclosed and had made efforts to cover it up. The Vice President was stunned, and as the tape transcripts were made public, impeachment in the House became a certainty, and key senators began to doubt the President could survive a Senate trial.

On August 6, Nixon called a meeting of his cabinet. To the surprise of all, he opened by talking about inflation and the global economy, but abruptly shifted to Watergate. His decision not to release the tapes had been based on national security concerns, he said. He relented, however, so that the House could vote on impeachment, having all the facts before them. Distracted by diplomacy with China, he had not focused on the presidential campaign, and “overeager” assistants had made bad decisions. But, Nixon said, he would not resign, and he asked for the cabinet’s private, if not public, support.

The room fell silent until Ford spoke up. He expressed sympathy for Nixon and his family, but said had he known beforehand what had recently been revealed, he would not have voiced such strong support. Accordingly, Ford informed the President, “I’ll have no further comment on the issue because I’m a party in interest.” He would, however, continue to support the Administration’s policies.

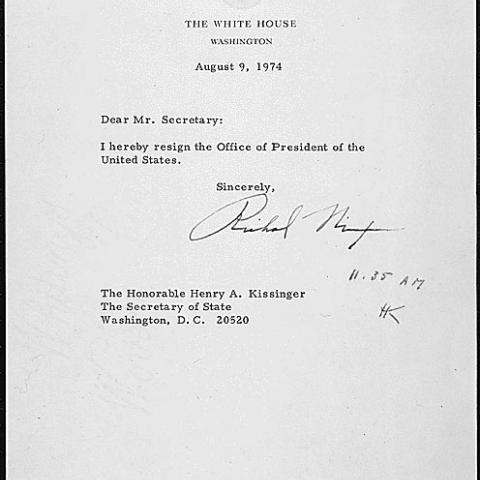

By August 8, Nixon’s remaining support had crumbled. He summoned Ford to the Oval Office. Sitting solemnly behind his desk with Ford seated to his right, Nixon told his Vice President of his intention to resign. “It’s in the best interest of the country. I won’t go into the details pro or con. I have made my decision.” He paused, then added, “Jerry, I know you’ll do a good job.”

Robert Bork was enjoying his job as President Nixon’s solicitor general. New to Washington, D. C., the University of Chicago Law School graduate and Yale professor had only recently been appointed to his post. On Saturday, October 20, 1973, Bork was to receive his baptism into the no-holds-barred ring of Washington politics. That evening word was passed that Nixon was angry. Watergate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox had rejected the president’s order to rescind the subpoena for White House tape recordings. Soon an order arrived from the president. Attorney General Elliot Richardson was to fire Cox. Troubled by what he saw as interference in an ongoing investigation that the president had promised to leave unfettered, Richardson refused the order and resigned. His subordinate, William Ruckelshaus, followed suit and quit rather than fire Cox. Bork, with no one behind him to whom the office could fall, assumed the role of acting Attorney General and obeyed the president’s order to fire Cox. He did so with the president’s assurance that the investigation would continue. “It is my expectation that the Department of Justice will continue with full vigor the investigations and prosecutions that had been entrusted to the Watergate special prosecution force,” Nixon wrote in his instructions to Bork. The deluge of anger that poured forth from lawmakers and the public over the event, dubbed the “Saturday Night Massacre”, underscored their lack of confidence in that assurance. Soon, another special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, was named, the investigation proceeded, and Nixon turned over the tapes. Bork continued to serve as solicitor general until 1977.

Documents

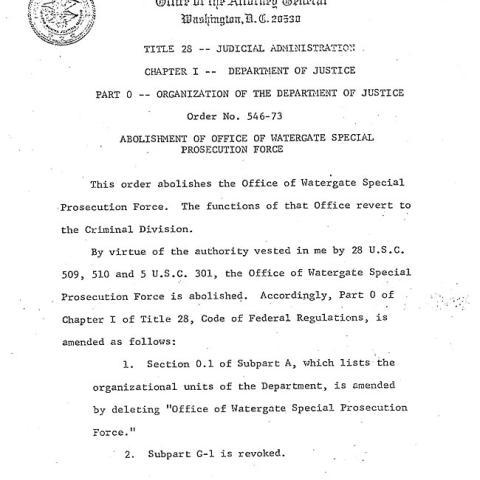

Transcript of Department of Justice Order No. 546-73

Office of the Attorney General

Washington , D.C. 20530

TITLE 28 JUDICIAL ADMINISTRATION

CHAPTER I DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

PART 0 ORGANIZATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

Order No. 546-73

ABOLISHMENT OF OFFICE OF WATERGATE SPECIAL PROSECUTION FORCE

This order abolishes the Office of Watergate Special Prosecution Force. The functions of that Office revert to the Criminal Division.

By virtue of the authority vested in me by 28 U.S.C. 509, 510 and 5 U.S.C. 301, the Office of Watergate Special Prosecution Force is abolished. Accordingly, Part 0 of Chapter I of Title 28, Code of Federal Regulations, is amended as follows:

1. Section 0.1 of Subpart A, which lists the organizational units of the Department, is amended by deleting Office of Watergate Special Prosecution Force.

2. Subpart G-1 is revoked.

Order No. 517-73 of May 31, 1973 , Order No. 518-73 of May 31, 1973 , Order No. 525-73 of July 8, 1973 , and Order No. 531-73 of July 31, 1973 , are revoked.

This order is effective as of October 21, 1973.

Date: 1973

Robert H. Bork [signed]

Acting Attorney General

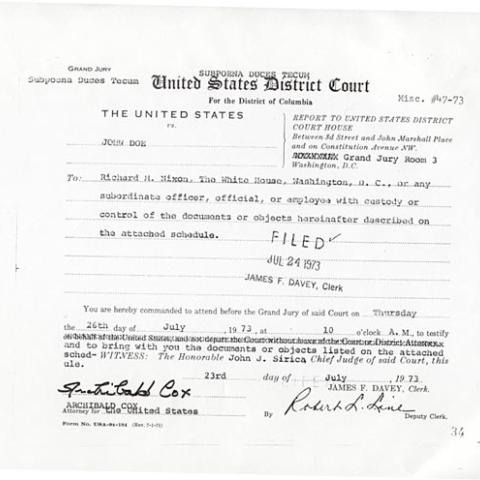

Transcript of Grand Jury subpoena issued by Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox to President Richard Nixon

GRAND JURY SUBPOENA DUCES TECUM

Subpoena Duces Tecum

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT For the District of Columbia

Misc. #47-73

THE UNITED STATES vs John Doe

REPORT TO UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT HOUSE

Between 3d Street and John Marshall Place and on Constitution Avenue NW.

Grand Jury Room 3

Washington , D.C.

To: Richard M. Nixon, The White House, Washington, D. C., or any subordinate officer, official, or employee with custody or control of the documents or objects hereinafter described on the attached schedule.

You are hereby commanded to attend before the Grand Jury of said Court on Thursday the 26 th day of July, 1973, at 10 o'clock A.M. to testify and to bring with you the documents or objects listed on the attached schedule. WITNESS: The Honorable John J. Sirica Chief Judge of said Court, this 23 rd day of July 1973.

JAMES F. DAVEY, Clerk

[signed]

ARCHIBALD COX

Attorney for the Untied States

by Robert L. Line [signed]

Deputy Clerk

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

GRAND JURY SUBPOENA DUCES TECUM

Dated July 23, 1973

Misc. #47-73

Schedule of Documents or Objects to be Produced by or on Behalf of Richard M. Nixon

- All tapes and other electronic and/or mechanical recordings or reproductions, and any memoranda, papers, transcripts or other writings, relating to:

- Meeting of June 20, 1972 , in the President's Executive Office Building (EOB�) Office involving Richard Nixon, John Erlichman and H. R. Haldeman from 10:30 a.m. to noon (time approximate).

- Telephone conversation of June 20, 1972 , between Richard Nixon and John N. Mitchell from 6:08 to 6:12 p.m.

- Meeting of June 30, 1972 , in the President's EOB Office, involving Messrs. Nixon, Haldeman and Mitchell from 12:55 to 2:10 p.m.

- Meeting of September 15, 1972 , in the President's Oval Office involving Mr. Nixon, Mr. Haldeman, and John W. Dean III from 5:27 to 6:17 p.m.

- Meeting of March 13, 1973 , in the President's Oval Office involving Messrs. Nixon, Dean, and Haldeman from 12:42 to 2:00 p.m.

- Meeting of March 21, 1973 , in the President's Oval Office involving Messrs. Nixon, Dean, and Haldeman from 10:12 to 11:55 a.m.

- Meeting of March 21, 1973 , in the President's EOB Office from 5:20 to 6:01 p.m. involving Messrs. Nixon, Dean, Ziegler, Haldeman and Erlichman.

- Meeting of March 22, 1973 , in the President's EOB Office from 1:57 to 3:43 p.m. involving Messrs. Nixon, Dean, Erlichman, Haldeman and Mitchell.

- Meeting of April 15, 1973 , in the President's EOB Office between Mr. Nixon and Mr. Dean from 9:17 to 10:12 p.m.

- The original two paragraph memorandum from W. Richard Howard to Bruce Kehrli, dated March 30, 1972, concerning the termination of Howard Hunt as a consultant and transfer to 1701, signed Dick, with handwriting on the top and bottom of the one-page memorandum indicating that it was placed there by Kehrli. (A copy of this memorandum was turned over to the Federal Bureau of Investigation on August 7, 1972, by James Rogers, Personnel Office, White House.)

- Original copies of all Political Matters Memoranda and all tabs or attachments thereto from Gordon Strachan to H. R. Haldeman between November 1, 1971, and November 7, 1972.

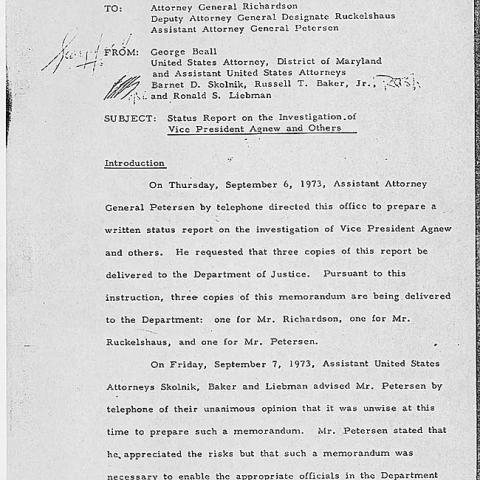

Transcript of Investigation Status Report filed in the U.S. Attorneys' Records on Spiro T. Agnew

MEMORANDUM

September 11, 1973

TO:

Attorney General Richardson

Deputy Attorney General Designate Ruckelshaus

Assistant Attorney General Petersen

FROM:

George Beall

United States Attorney, District of Maryland

and Assistant United States Attorneys

Barnet D. Skolnik, Russell T. Baker, Jr.,

and Ronald S. Liebman

SUBJECT:

Status Report on the Investigation of

Vice President Agnew and Others

Introduction

On Thursday, September 6, 1973 , Assistant Attorney General Petersen by telephone directed this office to prepare a written status report on the investigation of Vice President Agnew and others. He requested that three copies of this report be delivered to the Department of Justice. Pursuant to this instruction, three copies of this memorandum are being delivered to the Department: one for Mr. Richardson, one for Mr. Ruckelshaus, and one for Mr. Petersen.

On Friday, September 7, 1973 , Assistant United States Attorneys Skolnik, Baker and Liebman advised Mr. Petersen by telephone of their unanimous opinion that it was unwise at this time to prepare such a memorandum. Mr. Petersen stated that he appreciated the risks but that such a memorandum was necessary to enable the appropriate officials in the Department

336

Timeline

Trials and Tribulations

Overview

When Congress reconvened in January 1974, following its Christmas break, the House of Representatives compounded Nixon’s legal troubles. On February 6, it authorized the Judiciary Committee to investigate grounds for the impeachment of President Nixon. This added to investigations already underway by Judge Sirica and the grand jury, Special Prosecutor Jaworski and the Justice Department, and the work done by the Senate select committee on Watergate.

The legal noose tightened on March 1, when the United States District Court for the District of Columbia handed down a thirteen-count indictment against seven former White House aides, including Haldeman, Mitchell, Ehrlichman, and Charles Colson, for hindering its investigations. More damaging politically, Nixon himself was named an “unindicted co-conspirator” by the grand jury.

In April, responding to Jaworski’s demand for more tapes, the White House released edited transcripts. Nixon again appeared on TV to explain his stand against releasing the tapes. While not surprised by Jaworski and the judiciary committee’s insistence on receiving the actual tapes, the public was repulsed by the president’s language in the transcripts. The term “expletive deleted,” replacing coarse swearing, became an oft-repeated phrase in evening news casts and newspaper stories.

People

John Sirica was the son of Italian immigrants who moved from Connecticut to Washington, D. C. in search of a better life. There, young John labored as a trash collector, boxing coach, and acting instructor as he gained a formal education. In 1926 he passed the bar exam, was hired as an attorney in a small law firm, and lost his first thirteen court-appointed felony cases.

Sirica worked with the U. S. Attorney’s office during the Hoover administration. When he married in 1952, his close friend and former boxing champion, Jack Dempsey, served as his best man. Sirica increasingly became active in Republican politics and was appointed to the U. S. District Court for the District of Columbia in 1957. He soon gained the reputation as a maverick judge, at times irritable and careless, and earned the nickname “Maximum John” for his harsh rulings. It was not unusual for his decisions to be overturned during appeal.

In 1973 he presided over the Watergate trials. Quickly growing impatient with their pace and the lack of information yielded, Sirica adopted the controversial tactic of questioning the witnesses himself, and he instructed the jury to consider not only what happened, but also why it happened. Following the trial that saw five of the seven defendants plead guilty and two convicted, Sirica’s suspicions were confirmed, and the Watergate matter was transformed, when one of the burglars, James McCord, wrote a letter to the judge. In it he told how others in court had withheld information and that payments were made by high White House officials to ensure silence. Sirica made the letter public.

Within months, in Senate hearings, the existence of White House tapes was revealed. Sirica ordered the White House to turn over relevant tapes to his court. President Nixon claimed executive privilege, arguing issues of national security shielded the tapes from subpoena. The argument was quickly appealed to the Supreme Court, where the judge, who so often had his rulings overturned, was sustained by the nation’s highest court. The president had to turn over the tapes, and once their contents were revealed, Nixon’s fate was sealed.

An Eagle Scout, Navy veteran of World War II, and advertising executive, H. R. Haldeman had long admired Richard Nixon. It was during Congressman Nixon’s fight to expose Alger Hiss and his ties with Communism that Haldeman first took notice of his fellow Californian. In 1952, Haldeman’s father was one of the contributors to Nixon’s private campaign fund that almost derailed his spot as Eisenhower’s running mate. The younger Haldeman worked as an advance man in Nixon’s campaigns in 1956 and 1960 and managed his failed race for governor of California in 1962.

By 1968, Haldeman had earned Nixon’s confidence and loyalty. The president-elect appointed him chief of staff. Playing to Nixon’s reclusive management style, Haldeman became the “gatekeeper,” describing himself as the president’s “SOB.” Haldeman was a key player at many of the critical moments during the Watergate crisis. The June 20, 1972 tape containing the mysterious 18 ½ minute gap was a conversation between Haldeman and Nixon. The “smoking gun” tape, uncovered after the Supreme Court ordered Nixon to turn over relevant tapes, contained a conversation between the two plotting to instruct the CIA to tell the FBI to steer clear of investigating the Watergate break-in for reasons of national security.

Finally, after White House counsel John Dean implicated Haldeman and others in testimony before the Senate Watergate committee, he and Nixon’s domestic policy counsel, John Ehrlichman, resigned on April 30, 1973. With Haldeman’s resignation, the president lost more than his bulldog, more than his closest advisor. Following his speech to the nation in which he announced Haldeman’s dismissal, Haldeman called Nixon. Immediately, the president said, “I hope I didn’t let you down.” “No, sir,” replied Haldeman. The conversation, thick with emotion, stumbled on. “I don’t know whether you can call and get any reactions and call me back – like the old style. Would you mind?” Nixon asked. “I don’t think I can. I don’t –,” Haldeman began to answer. Nixon interrupted, “No, I agree.” The call continued for a few awkward moments, then Nixon, sensing it was spent, said for the third time, “I love you, as you know.” “Okay,” Haldeman said. “Like my brother,” Nixon added. In his memoirs, Nixon recalled, “from that day on the presidency lost all joy for me.”

Haldeman served eighteen months in prison for his Watergate-related crimes.

Mitchell was born in Detroit, Michigan and earned his law degree from Fordham University. He entered the Navy during World War II and commanded the PT boat unit in which John Kennedy served. Along the way, Mitchell earned two purple hearts and a silver star.

In 1967, Mitchell’s law firm merged with Richard Nixon’s. Mitchell left the new firm in 1968 to manager Nixon’s presidential campaign. Following his victory, Nixon appointed Mitchell to the post of Attorney General. Through the first administration, Mitchell oversaw the Justice Department’s handling of desegregation and affirmative action policies, then resigned in January 1972 to head Nixon’s Committee to Re-elect the President.

It was to Mitchell that Liddy and Magruder brought their ambitious “Gemstone” plan to steal and wring from their opposition political secrets. Mitchell balked at the scope and cost, in the end approving a scaled back, cheaper plan that included breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate hotel. In an effort to distance himself from what he called “the White House horrors,” Mitchell resigned from the CRP in June 1972, but was linked in a Washington Post story in September of that year to a secret campaign fund that underwrote the Watergate caper.

Mitchell was indicted by a federal grand jury in May 1973 and was convicted of conspiracy to obstruct justice, perjury, and obstruction of justice. He served 19 months in federal prison.

John Erhlichman was President Nixon’s top domestic affairs advisor. Together with Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, the two sought to protect the reclusive president, forming around him what others referred to as a “Berlin Wall.” Indeed, it was Ehrlichman and Haldeman who, in an effort to stop military information from leaking to the media, instructed Ehrlichman’s chief assistant, Egil Krogh, to oversee the “plumbers,” a secret group that undertook covert political operations. After Daniel Ellsberg secreted the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times, Ehrlichman instructed the plumbers to raid the California office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in search of incriminating evidence. Reporting on those efforts, Erhlichman tried not to reveal too much to the president. “We had one little operation. It’s been aborted out in Los Angeles which, I think, is better that you don’t know about,” he informed the president in September 1971.

After the Watergate investigation began, Nixon’s nominee for Director of the FBI, L. Patrick Gray, absorbed many of Congress’ blows during confirmation hearings. Subjected to heated criticism, especially over his relationship with the president’s legal counsel, John Dean, prospects for his approval looked bleak. Ehrlichman calculated political value in Congress eviscerating Gray’s nomination. It shifted the focus of Watergate from the White House. As Ehrlichman advised the president, better Gray be left “twisting, slowly, slowly in the wind.”

In April 1973, alienated from the White House by Nixon’s devotion to Haldeman and Ehrlichman and his own decision to freely testify before the grand jury and Senate committee, Dean implicated the president and his two advisors in the Watergate cover-up. On April 30, Nixon fired Dean and, following wrenching, emotional meetings with Ehrlichman and Haldeman, Nixon reluctantly accepted their resignations, along with the resignation of his Attorney General, Richard Kleindienst. Later convicted of conspiracy, obstruction of justice, making false statements, and other charges, Ehrlichman served eighteen months in federal prison.

Richard Nixon was a hardened veteran of the political arena. He had represented California in the House and Senate, where he earned a reputation as a fierce anti-Communist and a bare-knuckles campaigner. As Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president, Nixon had stayed on the ticket in 1952 only by countering charges of benefiting from a political slush fund through a last-minute televised appeal to the American public. After Ike’s two terms, Nixon secured the nomination in 1960, but lost by a razor-thin margin to his congressional classmate of 1946, John Kennedy. In 1962, Nixon ran for governor of California and again was defeated. But he recognized a political vacuum following Barry Goldwater’s landslide loss to Lyndon Johnson in 1964. His dogged foreign travels and nation-wide campaigning for Republican candidates in the 1966 mid-term election paid dividends two years later when the Republican party crowned his remarkable comeback by once again making him their presidential nominee.

In the national tumult that marred the year 1968, Nixon withstood the challenge of Vice President Hubert Humphrey who was saddled to an administration held responsible for an unpopular war and domestic unrest, and a strong third-party challenge by Alabama Governor George Wallace, who capitalized on racial discord. Nixon won the election with 43 percent of the popular vote (56 percent of the electoral vote). Two close presidential races intensified lessons Nixon drew from the rough and tumble of other political experiences. As he planned for re-election in 1972, he determined to leave nothing to chance. The campaign would be played by hardball rules, and Nixon would use every advantage the incumbency afforded him.

Conventional wisdom held that the Democrats would field a strong challenger in 1972. But by the end of the primaries, Ted Kennedy, Hubert Humphrey, and Edmund Muskie were gone, leaving the dark-horse Senator from South Dakota, George McGovern. The war in Vietnam dominated the campaign. As McGovern called for immediate withdrawal of U. S. troops and sharp reductions in defense spending, Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, sought to calm public unrest over the war by claiming that peace was near.

Yet even as he was driving toward an easy victory, Nixon was anything but calm. In response to the leaking of sensitive military information, Nixon had formed a special investigations unit called the “Plumbers” to plug those leaks. Not trusting his campaign to the normal Republican election framework, Nixon established the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP), headed by his former law partner and attorney general, John Mitchell. Through it the campaign was orchestrated, but a clandestine campaign was also waged. The Plumbers and others were used to raise large amounts of money, gather intelligence for political purposes, and spear the opposition.

Nixon crushed McGovern that November, winning 61 percent of the popular vote and all but 17 votes in the Electoral College. His overwhelming victory did not carry over to Capitol Hill, however, where his party lost seats in the Senate and enjoyed only modest gains in the House. In both chambers, the Republicans remained in the minority, a status that would prove costly as Nixon attempted to control the Watergate investigation in his second term. His greatest political victory was muted by this “third-rate burglary.” Though buoyed by the triumph, within six months of his January 1973 inauguration, the investigation that had been focused primarily on his campaign staff would be knocking on the door of his Oval Office, demanding he turn over until-then secret tape recordings. Once surrendered, his complicity in the crimes of his administration was revealed, and his presidency was doomed.

Documents

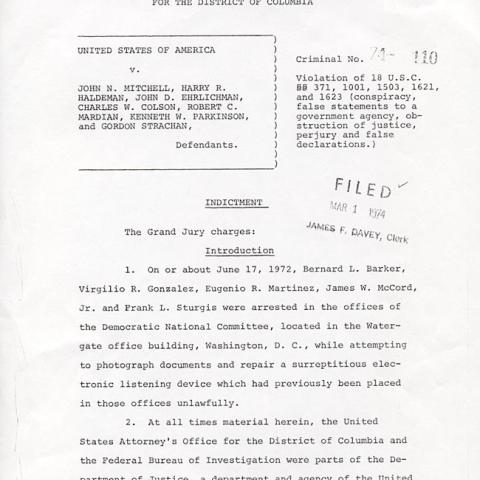

Image(s) of Indictment in United States of America v. John Mitchell, Harry R. Haldeman, John D. Ehrlichman, Charles Colson, Robert C. Mardian, Kenneth W. Parkinson and Gordon Strachan

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

v.

JOHN N. MITCHELL, HARRY R.

HALDEMAN, JOHN D. ERLICHMAN,

CHARLES W. COLSON, ROBERT C.

MARDIAN, KENNETH W. PARKINSON,

and GORDON STRACHAN,

Defendants.

Criminal No. 74-110

Violation of 18 U.S.C

§§ 371, 1001, 1503, 1621,

and 1623 (conspiracy,

false statements to a

government agency, ob-

struction of justice,

perjury and false

declarations.

INDICTMENT

The Grand Jury charges:

Introduction

1. On or about June 17, 1972, Bernard L. Barker, Virgilio R. Gonzalez, Eugenio R. Martinez, James W. McCord, Jr. and Frank L. Sturgis were arrested in the offices of the Democratic National Committee, located in the Watergate office building, Washington, D. C., while attempting to photograph documents and repair a surreptitious electronic listening device which had previously been placed in those offices unlawfully.

2. At all times material herein, the United States Attorney's Office for the District of Columbia and the Federal Bureau of Investigation were parts of the Department of Justice, a department and agency of the United States , and the Central Intelligence Agency was an agency of the United States .

3. Beginning on or about June 17, 1972, and continuing up to and including the date of the filing of this indictment, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the United States Attorney's Office for the District of Columbia were conducting an investigation, in conjunction with a Grand Jury of the Untied States District Court for the District of Columbia which had been duly empanelled and sworn on or about June 5, 972, to determine whether violations of 18 U.S.C. 371, 2511 and 22 D.C. Code 1801(b), and of other statutes of the United States and of the District of Columbia, had been committed in the District of Columbia and elsewhere, and to identify the individual or individuals who had committed, caused the commission of, and conspired to commit such violations.

4. on or about September 15, 1972, in connection with the said investigation, the Grand Jury returned an indictment in Criminal Case No. 1827-72 in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia charging Bernard L. Barker, Virgilio R. Gonzalez, E. Howard Hunt, Jr., G. Gordon Libby, Eugenio R. Martinez, James W. McCord, Jr., and Frank L. Sturgis with conspiracy, burglary and unlawful endeavor to intercept wire communications.

5. From in or about January 1969, to on or about March 1, 1972 , JOHN N. MITCHELL, the DEFENDANT, was Attorney General of the United States . From on or about April 9, 1972 , to on or about June 30, 1972 , he was Campaign Director of the Committee to Re-Elect the President.

6. At all times material herein up to on or about April 30, 1973 , HARRY R. HALDEMAN, the DEFENDANT, was Assistant to the President of the United States . 7. At all times material herein up to on or about April 30, 1973 , JOHN D. ERLICHMAN, the DEFENDANT, was Assistant for Domestic Affairs to the President of the United States .

8. At all times material herein up to on or about March 10, 1973 , CHARLES W. COLSON, the DEFENDANT, was Special Counsel to the President of the United States .

9. At all times material herein, ROBERT C. MARDIAN, the DEFENDANT, was an official of the Committee to Re-Elect the President.

10. From on or about June 21, 1972 , and at all times material herein, KENNETH W. PARKINSON, the DEFENDANT, was an attorney representing the Committee to Re-Elect the President.

11. At all times material herein up to in or about November 1972, GORDON STRACHAN, the DEFENDANT, was a Staff Assistant to HARRY R. HALDEMAN at the White House. Thereafter he became General Counsel to the United States Information Agency.

- 16 - 74-110

COUNT TWO

The Grand Jury further charges: