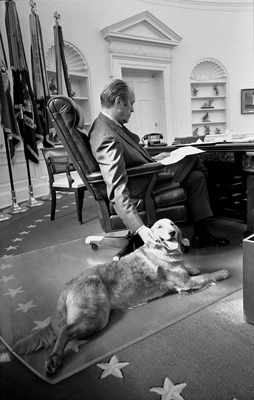

A1813-05 - President Ford and his golden retriever, Liberty, in the Oval Office. November 7, 1974.

A1813-05 - President Ford and his golden retriever, Liberty, in the Oval Office. November 7, 1974.

President Gerald Ford died at his California home on December 26, 2006. He was 93 years old.

Funeral services for President Ford were held at St. Margaret's Parish in Palm Desert, California; the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. and at Grace Episcopal Church in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Nearly 50,000 people signed the Condolence Books on the grounds of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum in Grand Rapids and Library in Ann Arbor beginning at 1:30 a.m. on Wednesday, December 27, 2006, through 5 p.m. Thursday, January 4, 2007.

An estimated 36,000 visited the U.S. Capitol Rotunda as President Ford lay in State. As President Ford lay in repose at the Museum, Tuesday afternoon through Wednesday morning, 62,000 people paid their respects, including the estimated 57,000 people who entered the queue through DeVos Place and waited patiently in line. In addition, an estimated 75,000 people lined the streets of Grand Rapids to welcome President Ford home on January 2, 2007 and during the funeral services on January 3, 2007.

The official period of mourning ended at sundown on Thursday, January 25, 2007. At this time flags were to be returned to full staff.

Following the services in Grand Rapids on January 3, 2007, President Ford was interred on the grounds of his Presidential Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The Gerald R. Ford and Betty B. Ford Burial Site is on the grounds of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum at 303 Pearl Street NW, Grand Rapids, MI 49504. The Burial Site is open to the public every day (except Thanksgiving, Christmas Day and New Year's Day) from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Parking is free. For more information, please call (616) 254-0400.

Since the passing of President Ford, citizens, organizations, and institutions have bestowed honors and tributes upon the former President, reflecting their gratitude and appreciation for his service to the country as a sailor, congressman, Vice President, and Thirty-Eighth President of the United States.

President George W. Bush's Eulogy for President Ford

President George W. Bush

National Cathedral

Washington, D.C.

January 2, 2007

Mrs. Ford, the Ford family; distinguished guests, including our Presidents and First Ladies; and our fellow citizens:

We are here today to say goodbye to a great man. Gerald Ford was born and reared in the American heartland. He belonged to a generation that measured men by their honesty and their courage. He grew to manhood under the roof of a loving mother and father -- and when times were tough, he took part-time jobs to help them out. In President Ford, the world saw the best of America -- and America found a man whose character and leadership would bring calm and healing to one of the most divisive moments in our nation's history.

Long before he was known in Washington, Gerald Ford showed his character and his leadership. As a star football player for the University of Michigan, he came face to face with racial prejudice when Georgia Tech came to Ann Arbor for a football game. One of Michigan's best players was an African American student named Willis Ward. Georgia Tech said they would not take the field if a black man were allowed to play. Gerald Ford was furious at Georgia Tech for making the demand, and for the University of Michigan for caving in. He agreed to play only after Willis Ward personally asked him to. The stand Gerald Ford took that day was never forgotten by his friend. And Gerald Ford never forgot that day either -- and three decades later, he proudly supported the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act in the United States Congress.

Gerald Ford showed his character in the devotion to his family. On the day he became President, he told the nation, "I am indebted to no man, and only to one woman -- to my dear wife." By then Betty Ford had a pretty good idea of what marriage to Gerald Ford involved. After all, their wedding had taken place less than three weeks before his first election to the United States Congress, and his idea of a "honeymoon" was driving to Ann Arbor with his bride so they could attend a brunch before the Michigan-Northwestern game the next day. (Laughter.) And that was the beginning of a great marriage. The Fords would have four fine children. And Steve, Jack, Mike, and Susan know that, as proud as their Dad was of being President, Gerald Ford was even prouder of the other titles he held: father, and grandfather, and great-grandfather.

Gerald Ford showed his character in the uniform of our country. When Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941, Gerald Ford was an attorney fresh out of Yale Law School, but when his nation called he did not hesitate. In early 1942 he volunteered for the Navy and, after receiving his commission, worked hard to get assigned to a ship headed into combat. Eventually his wish was granted, and Lieutenant Ford was assigned to the aircraft carrier, USS Monterey, which saw action in some of the biggest battles of the Pacific.

Gerald Ford showed his character in public office. As a young congressman, he earned a reputation for an ability to get along with others without compromising his principles. He was greatly admired by his colleagues and they trusted him a lot. And so when President Nixon needed to replace a vice president who had resigned in scandal, he naturally turned to a man whose name was a synonym for integrity: Gerald R. Ford. And eight months later, when he was elevated to the presidency, it was because America needed him, not because he needed the office.

President Ford assumed office at a terrible time in our nation's history. At home, America was divided by political turmoil and wracked by inflation. In Southeast Asia, Saigon fell just nine months into his presidency. Amid all the turmoil, Gerald Ford was a rock of stability. And when he put his hand on his family Bible to take the presidential oath of office, he brought grace to a moment of great doubt.

In a short time, the gentleman from Grand Rapids proved that behind the affability was firm resolve. When a U.S. ship called the Mayaguez was seized by Cambodia, President Ford made the tough decision to send in the Marines -- and all the crew members were rescued. He was criticized for signing the Helsinki Accords, yet history has shown that document helped bring down the Soviet Union, as courageous men and women behind the Iron Curtain used it to demand their God-given liberties. Twice assassins attempted to take the life of this good and decent man, yet he refused to curtail his public appearances. And when he thought that the nation needed to put Watergate behind us, he made the tough and decent decision to pardon President Nixon, even though that decision probably cost him the presidential election.

Gerald Ford assumed the presidency when the nation needed a leader of character and humility -- and we found it in the man from Grand Rapids. President Ford's time in office was brief, but history will long remember the courage and common sense that helped restore trust in the workings of our democracy.

Laura and I had the honor of hosting the Ford family for Gerald Ford's 90th birthday. It's one of the highlights of our time in the White House. I will always cherish the memory of the last time I saw him, this past year in California. He was still smiling, still counting himself lucky to have Betty at his side, and still displaying the optimism and generosity that made him one of America's most beloved leaders.

And so, on behalf of a grateful nation, we bid farewell to our 38th President. We thank the Almighty for Gerald Ford's life, and we ask for God's blessings on Gerald Ford and his family.

Vice President Richard Cheney's Eulogy for President Ford

Vice President Richard Cheney

U.S. Capital Rotunda

Washington, D.C.

December 30, 2006

Mrs. Ford, Susan, Mike, Jack, and Steve; distinguished guests; colleagues and friends; and fellow citizens:

Nothing was left unsaid, and at the end of his days, Gerald Ford knew how much he meant to us and to his country. He was given length of years, and many times in his company we paid our tributes and said our thanks. We were proud to call him our leader, grateful to know him as a man. We told him these things, and there is comfort in knowing that. Still, it is an ending. And what is left now is to say goodbye.

He first stood under this dome at the age of 17, on a high school tour in the Hoover years. In his congressional career, he passed through this Rotunda so many times -- never once imagining all the honors that life would bring. He was an unassuming man, our 38th President, and few have ever risen so high with so little guile or calculation. Even in the three decades since he left this city, he was not the sort to ponder his legacy, to brood over his place in history. And so in these days of remembrance, as Gerald R. Ford, goes to his rest, it is for us to take the measure of the man.

It's hard to imagine that this most loyal of men began life as an abandoned child, facing the world alone with his mother. He was devoted to her always, and also to the fine man who came into their lives and gave the little boy a name he would carry into history. Gerald and Dorothy Ford expected good things of their son. As it turned out, there would be great things, too -- in a journey of 93 years that would fill them with loving pride.

Jerry Ford was always a striver -- never working an angle, just working. He was a believer in the saying that in life you make your own luck. That's how the Boy Scout became an Eagle Scout; and the football center, a college all-star; and the sailor in war, a lieutenant commander. That's how the student who waited tables and washed dishes earned a law degree, and how the young lawyer became a member of the United States Congress, class of 1948. The achievements added up all his life, yet he was known to boast only about one. I heard it once or twice myself -- he said he was never luckier than when he stepped out of Grace Episcopal Church in Grand Rapids with a beautiful girl named Betty as his bride.

Fifty-eight years ago, almost to the day, the new member from Michigan's fifth district moved into his office in the Cannon Building, and said his first hello to the congressman next door, John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts. They belonged to a generation that came early to great duties, and took up responsibilities readily, and shared a confidence in their country and its purposes in the world.

In that 81st Congress were four future Presidents, and others who wished for that destiny. For his part, Mr. Ford of Michigan aspired only to be Speaker of the House, and by general agreement he would have made a fine one. Good judgment, fair dealing, and the manners of a gentleman go a long way around here, and these were the mark of Jerry Ford for a quarter century in the House. It was a Democrat, the late Martha Griffiths, who said, "I never knew him to make a dishonest statement nor a statement part-true and part-false, and I never heard him utter an unkind word."

Sometimes in our political affairs, kindness and candor are only more prized for their scarcity. And sometimes even the most careful designs of men cannot improve upon history's accident. This was the case in the 62nd year of Gerald Ford's life, a bitter season in the life of our country.

It was a time of false words and ill will. There was great malice, and great hurt, and a taste for more. And it all began to pass away on a Friday in August, when Gerald Ford laid his hand on the Bible and swore to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. He said, "You have not elected me as your President by your ballot, and so I ask you to confirm me as your President with your prayers."

What followed was a presidency lasting 895 days, and filled with testing and trial enough for a much longer stay. Even then, amid troubles not of his own making, President Ford proved as worthy of that office as any who had ever come before. He was modest and manful; there was confidence and courage in his bearing. In judgment, he was sober and serious, unafraid of decisions, calm and steady by nature, always the still point in the turning wheel. He assumed power without assuming airs; he knew how to treat people. He answered courtesy with courtesy; he answered discourtesy with courtesy.

This President's hardest decision was also among his first. And in September of 1974, Gerald Ford was almost alone in understanding that there can be no healing without pardon. The consensus holds that this decision cost him an election. That is very likely so. The criticism was fierce. But President Ford had larger concerns at heart. And it is far from the worst fate that a man should be remembered for his capacity to forgive.

In politics it can take a generation or more for a matter to settle, for tempers to cool. The distance of time has clarified many things about President Gerald Ford. And now death has done its part to reveal this man and the President for what he was.

He was not just a cheerful and pleasant man -- although these virtues are rare enough at the commanding heights. He was not just a nice guy, the next-door neighbor whose luck landed him in the White House. It was this man, Gerald R. Ford, who led our republic safely through a crisis that could have turned to catastrophe. We will never know what further unravelings, what greater malevolence might have come in that time of furies turned loose and hearts turned cold. But we do know this: America was spared the worst. And this was the doing of an American President. For all the grief that never came, for all the wounds that were never inflicted, the people of the United States will forever stand in debt to the good man and faithful servant we mourn tonight.

Thinking on all this, we are only more acutely aware of a time in our lives and of its end. And we can be certain that Gerald Ford would now ask only that we remember his wife. Betty, the President was not a hard man to read, and to his friends nothing was more obvious than the source of his great happiness. It was you. And all the good that you shared, Betty, all the good that you did together, has not gone away. All of that is forever.

There is a time to every purpose under Heaven. In the years of Gerald Rudolph Ford, it was a time to heal. There is also, in life, a time to part, when those who are dear to us must go their way. And so for now, Mr. President -- farewell. We will always be thankful for your good life. In Almighty God, we place our confidence. And to Him we confirm you, with our love and with our prayers.

President Jimmy Carter's Eulogy for President Ford

Former President Jimmy Carter

Grace Episcopal Church

Grand Rapids, Michigan

January 3, 2007

"For myself and for our nation, I want to thank my predecessor for all he has done to heal our land."

Those were the first words I spoke as president. And I still hate to admit that they received more applause than any other words in my inaugural address.

You learn a lot about a man when you run against him for president, and when you stand in his shoes, and assume the responsibilities that he has borne so well, and perhaps even more after you both lay down the burdens of high office and work together in a nonpartisan spirit of patriotism and service.

My staff and my diary notes, as I prepared for this eulogy, reveal a list of more than 25 different projects on which Jerry and I have shared leadership responsibilities.

He and I were both amused by a "New Yorker" cartoon a couple years ago. This little boy is looking up at his father. And he says, "Daddy, when I grow up, I want to be a former president."

Jerry and I frequently agreed that one of the greatest blessings that we had, after we left the White House during the last quarter-century was the intense personal friendship that bound us together.

During our closely contested political campaign, as Don just reminded me, we habitually referred to each other as "my distinguished opponent." And, for my own benefit, while I was president, I kept him fully informed about everything that I did in the domestic or international arena.

In fact, he was given a thorough briefing almost every month from the head of my White House staff or my national security adviser. And Jerry never came to the Washington area without being invited to have lunch with me at the White House.

We always cherished those memories of now perhaps a long-lost bipartisan interrelationship.

Jerry Ford and I shared a lot. We both served in the U.S. Navy, he on battleships, I on submarines, as junior officers. In fact, it was my profession. And we both enjoyed our unexpected promotion to commander in chief.

Each of us had three sons. And then our prayers were answered… and we had a daughter.

And we both married women who were good-looking, smart, and extremely independent.

As president, I relished his sound advice. And he often, although, I must say, reluctantly, departed from the prevailing opinion of his political party to give me support on some of my most difficult challenges.

For many of these, of course, he had helped to lay the foundation, including the Panama Canal treaties, nuclear armaments control with the Soviet Union, normalized diplomatic relations with China, and also the Camp David accords.

In fact, on a helicopter in flight from Camp David back to Washington, President Anwar Sadat, Prime Minister Menachem Begin and I made one telephone call, to Gerald Ford, to tell him that we had reached peace between Israel and Egypt.

President Ford and I also shared a commitment to force the Soviet Union to comply with its promise to respect human rights within the Helsinki agreement, which gave strength to brave dissidents behind the Iron Curtain, and helped to undermine Soviet tyranny from within.

Our mutual respect, which I have described, blossomed into a valued personal friendship during our shared trip to attend the funeral of President Anwar Sadat in Egypt. We formed a personal bond while lamenting on the difficulty of unexpectedly defeated candidates trying to raise money to build presidential libraries.

That's what bound us together most firmly, I think, for the rest of our days.

In the early days of the Carter Center, Jerry joined me as co-chairman in all of our important conferences and projects. And I never declined an opportunity to help him with his own post- presidential plans.

We enjoyed each other's private company. And he and I commented often that, when we were traveling somewhere in an automobile or airplane, we hated to reach our destination, because we enjoyed the private times that we had together.

More -- one of our most successful and little-known joint efforts, by the way, was agreeing on how to respond to the literally hundreds of invitations from people who claimed that all the presidents were going to participate in an event. And, after a private telephone conversation, we would quickly let them know that at least two of us would not be attending.

Yesterday, on the flight here from Washington, Rosalynn and I were thrilled when one of his sons came to tell us that the greatest gift he received from his father was his faith in Jesus Christ.

It is true that Jerry and I shared a common commitment to our religious faith, not just in worshipping the same savior, but in attempting, in our own personal way, to achieve reconciliation within our respective denominations.

We took to heart the admonition of the Apostle Paul that Christians should not be divided over seemingly important, but tangential issues, including sexual preferences and the role of women in the church, things like that.

We both felt that Episcopalians, Baptists and others should live together in harmony, within the adequate and common belief that we are saved by the grace of God through our faith in Jesus Christ, that we are saved by the grace of God through our faith in Jesus Christ.

One of my proudest moments was at the commemoration of the 200th birthday of the White House, when two noted historians both declared that the Ford-Carter friendship was the most intensely personal between any two presidents in history.

This close relationship extended to our spouses, as Betty worked on drug and alcohol abuse, and Rosalynn addressed the challenges of mental illness. And, when those two women descended on Washington together, few members of Congress could resist their combined lobbying assault.

The four of us learned to love each other.

In closing, let me extend, on behalf of Rosalynn and me and Jack and Chip and Jeffrey and Amy, and our 11 grandchildren, and one great- grandson, our personal sympathy and love to Betty and Mike and Jack and Steve and Susan, and all of your extended family.

The tens of thousands of people who lined the highway yesterday and today were expressing this mutual love which we share for President Jerry Ford.

I still don't know any better way to express it than the words I used almost exactly 30 years ago. For myself and for our nation, I want to thank my predecessor for all he did to heal our land.

President George H.W. Bush's Eulogy for President Ford

Former President George H.W. Bush

National Cathedral

Washington, D.C.

January 2, 2007

Well, as the story goes, Gerald Ford was a newly minted candidate for the United States House of Representatives in June of 1948 when he made plans with a reporter to visit the dairy farmers in western Michigan’s Fifth Congressional District. It was pouring rain that particular day and neither the journalist nor the farmers had expected the upstart candidate to keep his appointment. And yet he showed up on time because, as he explained to the journalist, “they milk cows every day and, besides that, I promised.”

Long before he arrived in Washington, Gerald Ford’s word was good. During the three decades of public service that followed his arrival in our nation’s capital, time and again he would step forward and keep his promise even when the dark clouds of political crisis gathered over America.

After a deluded gunman assassinated President Kennedy, our nation turned to Gerald Ford and a select handful of others to make sense of that madness. And the conspiracy theorists can say what they will, but the Warren Commission report will always have the final definitive say on this tragic matter. Why? Because Jerry Ford put his name on it and Jerry Ford’s word was always good.

A decade later, when scandal forced a vice president from office, President Nixon turned to the minority leader in the House to stabilize his administration because of Jerry Ford’s sterling reputation for integrity within the Congress. To political ally and adversary alike, Jerry Ford’s word was always good.

And, of course, when the lie that was Watergate was finally laid bare, once again we entrusted our future and our hopes to this good man. The very sight of Chief Justice Berger administering the oath of office to our 38th president instantly restored the honor of the Oval Office and helped America begin to turn the page on one of our saddest chapters.

As Americans we generally eschew notions of the indispensable man, and yet during those traumatic times, few if any of our public leaders could have stepped into the breach and rekindled our national faith as did President Gerald R. Ford.

History has a way of matching man and moment. And just as President Lincoln’s stubborn devotion to our Constitution kept the Union together during the Civil War, and just as F.D.R.’s optimism was the perfect antidote to the despair of the Great Depression, so too can we say that Jerry Ford’s decency was the ideal remedy for the deception of Watergate.

For this and for so much more, his presidency will be remembered as a time of healing in our land. In fact, when President Ford was choosing a title for his memoirs, he chose words from the book of Ecclesiastes.c

Here was the verse:

“To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven.

“A time to be born, a time to die.

“A time to kill, and a time to heal.

“A time to weep, and a time to laugh.

“A time to mourn, and a time to dance.”

He acknowledged that he was no saint. To know Jerry was to know a Norman Rockwell painting come to life. An avuncular figure, quick to smile, frequently with his pipe in his mouth. He could be tough. He could be tough as nails when the situation warranted. But he also had a heart as big and as open as the Midwest plains on which he was born. And he imbued every life he touched with his understated gentility.

When we served together in the House of Representatives years ago, I watched from the back bench — I watched this good man — and even from way back there I could see the sterling leadership qualities of Jerry Ford. And later, after I followed his footsteps into the Oval Office, he was always supportive.

On the lighter side, Jerry and I shared a common love of golf and also a reputation for suspect play before large crowds.

“I know I’m playing better golf,” President Ford once reported to friends, “because I’m hitting fewer spectators.”

He had a wonderful sense of humor and even took it in stride when Chevy Chase had to make the entire world think that this terrific, beautifully coordinated athlete was actually a stumbler. Ford said it was funny. He wrote it in his memoir.

I remember that lesson well, since being able to laugh at yourself is essential in public life. I’d tell you more about that, but as Dana Carvey would say: “Not gonna do it. Wouldn’t be prudent.”

In the end, we are all God’s children. And on this bittersweet day we can take solace that the Lord has come and taken this good man by the hand and led him home to heaven.

It is plain to see how the hand of providence spared Jerry in World War II and later against two assassination attempts. And for that we give thanks. It is just as plain to see how the same hand directed this good man to lead a life of noble purpose, a life filled with challenge and accomplishment, a life indelibly marked by honor and integrity. And today we give thanks for that, too.

May Almighty God bless the memory of Gerald R. Ford, keep him firm in the hearts of his countrymen. And may God bless his wonderful family.

Senator Ted Steven's Eulogy for President Ford

Senator Ted Stevens

U.S. Capital Rotunda

Washington, D.C.

December 30, 2006

Mrs. Ford, Michael, Jack, Steven, and Susan, distinguished guests, members of the Ford family, friends of Gerald Ford in America and throughout the world:

Tonight we say good-bye to a true gentleman, an exceptional leader, and our good friend, President Gerald Ford.

In our nation’s history, only nine men have been called upon to assume the mantle of the presidency by succession. Even among these chosen few, Gerald Ford stands out as exceptional for only one man has assumed both the vice presidency and the presidency.

When he took his oath as president, we were a people shaken by disbelief, racked with cynicism, and paralyzed by doubt. Then President Ford’s voice – gentle but firm – told us, “We must go forward now together.”

In our nation’s darkest hour, Gerald Ford lived his finest moment. Guided by his conscience, informed by our history, supported by the love and friendship of his wife, Betty, he was the man the hour required. He knew the road toward national healing began with courage to forgive. He reminded us: while the presidency may be a human institution, there is great nobility in its humanity.

While his path to office was unlikely, history will know Gerald Ford’s presidency was no accident. By the time he took the oath of office, he had achieved everything he set his mind to do: He earned the rank of Eagle Scout and became the University of Michigan football team’s most valuable player. During World War II, he served our country with distinction and was one of the men who inspired the title “the Greatest Generation.” He honorably served the people of Michigan in the U.S. House of Representatives.

A “Man of the House,” Jerry Ford stepped proudly into his role as Vice President, and the Senate welcomed him as the President of our chamber. While he never voted to break a tie in the Senate, he was known to all of us as a person full of friendship, willing to sit and discuss issues at the request of any Senator.

President Ford achieved the goals he sought, but history will remember most, how, in its hour of need, our nation sought him. As our 38th President, Gerald Ford stood ready to faithfully execute his office. In doing so, he woke us and told us – and I quote – “Our long national nightmare is over.”

He was the steady hand in the storm, an honest broker of compromise. he became a great leader – an example for others to follow. President Ford understood the unique circumstances of his moment in history. he strove not to placate some, but to serve all. In so doing, he showed us there were still things which were good and honest and true. He restored our faith in our leaders, and he ensured the office of the presidency was an institution worthy of the people it serves.

We here honor a leader for America and the world. President Ford fought high inflation and unemployment, completed the process of bringing our troops home from Vietnam, set the framework for the Middle East peace accords, and began a new era of cooperation and friendship with Japan. He was deeply beloved by the people of Alaska for signing legislation to protect the marine resources within 200 miles of our shores.

No one should suggest the tasks before him were easy. President Ford was scrutinized, questioned, and criticized. He was tested by the fire of public opinion. Few have remained hopeful in the face of such adversity, but Gerald Ford’s optimism about America never wavered. He faced each challenge with bravery and courage matched only by his wife Betty, a woman who literally offered hope to millions of Americans by candidly sharing her experiences and inner strength.

President Ford once said, “I am indebted to no man, and only one woman – my dear wife.” That debt our nation shares, for Betty Ford is one of the most remarkable first ladies to have ever graced the White House.

In the days since President Ford’s passing, many words have been spoken and many statements published alluding to the tremendous character with which he approached his nearly three decades in public life. It was a character I witnessed firsthand when, as chair of our Senate Campaign Committee, I worked closely with President Ford and his running mate, Senator Bob Dole. During that time, I developed a deeper understanding and greater appreciation for Jerry Ford as a man, a father, and a husband. As was his running mate, Bob Dole, he was deeply committed to our democracy. absolute honesty, integrity, and openness were the hallmarks of his career. They are now the legacy and the challenge he leaves to us.

President Ford’s life is a reminder to those who serve this democracy – under this Capitol dome and elsewhere – that we are – for a time – the keepers of this great American experiment. Good stewardship requires us to see beyond party, beyond division, beyond personal aspirations.

President Ford once said: “The Constitution is the bedrock of all of our freedoms. Guard and cherish it, keep honor and order in your own house, and the Republic will endure.”

It will be a fitting tribute to our good friend’s memory to make this truth our intention and our purpose.

Upon taking the oath of office, President Ford asked our nation to pray for him. In the next two days, Americans will come to this Rotunda to join us in praying for him once again. The line of visitors saying farewell has literally stretched from sea to shining sea – from California to our nation’s capitol. And it will end in Michigan, where the prayers of our grateful nation will carry President Ford on his final journey home.

Secretary Henry Kissinger's Eulogy for President Ford

Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

National Cathedral

Washington, D.C.

January 2, 2007

According to an ancient tradition, God preserves humanity despite its many transgressions because at any one period there exist 10 just individuals who, without being aware of their role, redeem mankind.

Gerald Ford was such a man. Propelled into the presidency by a sequence of unpredictable events, he had an impact so profound it’s rightly to be considered providential.

Unassuming and without guile, Gerald Ford undertook to restore the confidence of Americans in their political institutions and purposes. Never having aspired to national office, he was not consumed by driving ambition. In his understated way, he did his duty as a leader, not as a performer playing to the gallery.

Gerald Ford had the virtues of small-town America: sincerity, serenity and integrity. As it turned out, the absence of glibness and his artless decency became a political asset, fostering an unusual closeness to leaders around the world, which continued long after he left office.

In recent days, the deserved commentary on Gerald Ford’s character has sometimes obscured how sweeping and lasting were his achievements.

Gerald Ford’s prudence and common sense kept ethnic conflicts in Cyprus and Lebanon from spiraling into regional war.

He presided over the final agony of Indochina with dignity and wisdom.

In the Middle East, his persistence produced the first political agreement between Israel and Egypt.

He helped shape the act of the Helsinki European Security Conference, which established an internationally recognized standard for human rights, now generally accepted as having hastened the collapse of the former Soviet empire.

He sparked the initiative to bring majority rule to southern Africa, a policy that was a major factor in ending colonialism there.

In his presidency, the International Energy Agency was established, which still forces cooperation among oil-consuming nations.

Gerald Ford was one of the founders of the continuing annual economic summit among the industrial democracies.

Throughout his 29 months in office, he persisted in conducting negotiations with our principal adversary over the reduction and control of nuclear arms. Gerald Ford was always driven by his concern for humane values. He stumped me in his fifth day in office when he used the first call made by the Soviet ambassador to intervene on behalf of a Lithuanian seaman who four years earlier had in a horrible bungle been turned over to Soviet authorities after seeking asylum in America. Against all diplomatic precedent and, I must say, against the advice of all experts, Gerald Ford requested that the seaman, a Soviet citizen in a Soviet jail, not only be released but be turned over to American custody. Even more amazingly, his request was granted.

Throughout the final ordeal of Indochina, Gerald Ford focused on America’s duty to rescue the maximum number of those who had relied on us. The extraction of 150,000 refugees was the consequence. And typically Gerald Ford saw it as his duty to visit one of the refugee camps long after public attention had moved elsewhere.

Gerald Ford summed up his concern for human values at the European Security Conference, when looking directly at Brezhnev he proclaimed America’s deep devotion to human rights and individual freedoms. “To my country,” he said, “they’re not clichés or empty phrases.”

Historians will debate for a long time over which president contributed most to victory in the cold war. Few will dispute that the cold war could not have been won had not Gerald Ford emerged at a tragic period to restore equilibrium to America and confidence in its international role.

Sustained by his beloved wife, Betty, and with the children to whom he was devoted, Gerald Ford left the presidency with no regrets, no second-guessing, no obsessive pursuit of his place in history.

For his friends, he leaves an aching void. Having known Jerry Ford and having worked with him will be our badge of honor for the rest of our lives.

Early in his administration, Gerald Ford said to me: “I get mad as hell, but I don’t show it, when I don’t do as well as I should. If you don’t strive for the best, you will never make it.”

We are here to bear witness that Jerry Ford always did his best, and that his best proved essential to renew our society and restore hope to the world.

Donald Rumsfeld's Eulogy for President Ford

Former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld

Grace Episcopal Church

Grand Rapids, Michigan

January 3, 2007

Reverend, clergy, President and Mrs. Carter, Mr. Vice President and Lynne, honored guests and friends of Gerald Rudolph Ford.

There's an old saying in Washington that every member of the United States Congress looks in the mirror and sees a future president. Well, Jerry Ford was different. I suspect that when he looked in a mirror, even after he became president, he saw a citizen and a public servant.

A few days ago a neighbor offered an insight, saying, "He was one of us." And he was. And that made him special and needed in a dark and dangerous hour for our nation.

No matter how mean-spirited or partisan Washington became -- and let's not forget that as president, Gerald Ford, as other presidents, was roundly criticized and belittled, but he never lowered himself to that level.

Mr. Vice President, you will recall well his strong disapproval when his longtime friend, Congressman George Mahon, a Democrat, was criticized. And his deep disappointment when, for a variety of reasons, he was unable to attend a function honoring his political rival but close friend, then Speaker of the House of Representatives, Tip O'Neill. In the Oval Office, working on his transition to the presidency, we saw him welcome advice from Democrats and Republicans alike in those very early days.

But the advice he valued most, as he put it, "Was that which comes from my wife." Betty, as I recall, your advice was unvarnished, sometimes unsolicited, and almost always right on the mark. Indeed, everyone who knew him could see that Gerald Ford seemed to marvel every day at his great good fortune at having met and married Elizabeth Bloomer Ford.

Betty was a first lady like no other, an inspiration for truly millions that she never met and a rock of support for a husband who relied greatly on her wisdom, her candor, and, indeed, her personal courage. Betty, we thank you for your devotion to him, to our country, and to the millions of Americans who have benefited because you have touched their lives.

Mike, Jack, Steve and Susan, you and your children are in our prayers today also. You strengthened and sustained your dad during a profound and turbulent time. And your country is grateful for that.

You know, a wonder of America is that its future presidents can rise from unlikely places: a log cabin in Kentucky, a haberdashery in Missouri, an ice creamery in Kansas, or a paint shop in Michigan.

In fact, a visit to this city in the 1920s or 30s might well have come across a towheaded boy cleaning paint cans or selling soda at the amusement park to earn some extra money during the Depression.

Jerry Ford had a self-described fiery demeanor. He said because of it, his mother made a lot of friends, all of the mothers of the kids that he had gotten into scraps with. But if he had a certain "vinegar," he was also brimming with promise. He demonstrated that at Michigan, at Yale, as a volunteer in the Navy stationed aboard the USS Monterey.

When Joyce and I visited him just after Thanksgiving, he told us about the time that the USS Monterey, the aircraft carrier he served on in World War II, encountered a typhoon which heavily damaged the ship and nearly threw him overboard. I doubt that he ever imagined that 30 later, he would be at the head of a different kind of ship, swept by a different kind of storm, and that America would be depending on his steady and trusted hand at the helm.

When I joined Gerald Ford as a member of Congress in 1962, I found a skillful legislator who had earned the respect of his colleagues. He was energetic in his desire to serve and to contribute, but he did not wake up every morning wondering how he could get ahead. In fact, in 1964, Betty will remember that a small group of us had to work very, very hard to persuade Jerry Ford to run for minority leader of the United States House of Representatives. And I was able to see him work skillfully to achieve passage of the historic civil rights legislation during the 1960s.

Later, as White House chief of staff, I was standing next to President Ford during two assassination attempts that stunned an already traumatized country, which he handled with courage, with poise, and, I should add, with good humor.

He was a patriot who knew that freedom is precious and that it comes at a cost. I'm grateful that I was serving last year when the Navy considered naming a new aircraft carrier class the USS Gerald R. Ford, a decision to be announced some time later this month, I'm told. And, without giving away any secrets, I can report that, during that visit with President Ford, I brought him a cap with the USS Gerald R. Ford emblazoned across the top of it. How fitting it will be that the name Gerald R. Ford will patrol the high seas for decades to come, in the defense of the nation he loved so much.

Over the past few days, in the midst of our mourning, Americans have searched for the words to best describe Jerry Ford, the man, and the Ford era. My own thoughts are drawn to the profound and historic legacy he created in his nearly 900 days as president. It takes time and distance before one can truly measure an event or even an era, but many here remember well what our country was like on that day that Gerald Ford took the presidency.

The pressures were enormous. The stakes were high. The world was watching. And the American people were holding their breath, wondering what would happen next.

The words President Ford used to reassure our country and the American people were plain and they were straightforward. His sincerity gave them eloquence. Even in a country coarsened by skepticism, few doubted that the gentleman from Michigan would keep his word.

That was his special magic. He was then, and remains today, the only person who took office without having been elected to either the presidency or the vice presidency. He had no national base. He had no political platform, no campaign team, no time to prepare for his truly awesome responsibilities. In a sense, he stepped into an airplane in full flight as the command pilot, without even knowing the crew.

Our Cold War enemies were searching for signs of vulnerability. So the American president had to be strong.

Our nation was reeling from bitterness and suspicion. So the president needed to be comforting and reassuring.

The economy was fragile, and our national political institutions were shaken. So the president had to be decisive and confident.

Our country generally seems blessed to find the right leader at the right time. Through that special providence, the times found Gerald Ford. Because Gerald Ford was there to restore the strength of the presidency, to rebuild our defenses, and to demonstrate firmness and clarity, America could again, in Lincoln's words, "stand as the last, best hope of Earth."

He reminded Americans of who they were. And he put us on the right path, when the way ahead was, at best, uncertain. And, all things considered, those are probably most lasting and profound contributions that a leader can make.

It's commonly said that President Ford healed the nation. And he did. Like all great leaders, he knew victory, and he knew loss. After a long and tough campaign, one might have expected him to carry some bitterness over his narrow defeat for election in his own right.

Instead, he remembered the cloudy skies over Washington on the day of -- he first entered the White House. And, as his plane left the city on his last day as president, he recalled that the sun was shining brightly.

He said, "I couldn't see a cloud anywhere, and I felt glad about that."

Today, we say goodbye to a leader, a husband, a father, a grandfather, and, for so many of the people here today, a friend. And we take comfort knowing that Gerald Ford is now in a place greater than even the country he led, a kingdom everlasting, and without a cloud in sight. It is a place where, in the words of the scriptures, "the lord God will wipe away tears from all faces."

May God bless Gerald Ford and his strong and loving family. And may God bless the country he loves so much, served so well, and did so much to heal and strengthen.

Journalist Tom Brokaw's Eulogy for President Ford

Journalist Tom Brokaw

National Cathedral

Washington, D.C.

January 2, 2007

Mrs. Ford, members of the Ford family, President and Mrs. Bush, Vice President and Mrs. Cheney, President and Mrs. Bush, President and Mrs. Carter, President and Mrs. Clinton, distinguished guests, my fellow Americans, it’s a great privilege and an honor for me to be here.

For the past week, we have been hearing the familiar lyrics of the hymns to the passing of a famous man, the hosannas to his decency, his honesty, his modesty and his steady-as-she-goes qualities. It’s what we’ve come to expect on these occasions.

But this time there was extra value, for in the case of Gerald Ford, these lyrics have the added virtue of being true.

Sometimes there are two versions to these hymns — one public and one private, separate and discordant. But in Gerald Ford, the man he was in public, he was also that man in private.

Gerald Ford brought to the political arena no demons, no hidden agenda, no hit list or acts of vengeance. He knew who he was and he didn’t require consultants or gurus to change him. Moreover, the country knew who he was and despite occasional differences, large and small, it never lost its affection for this man from Michigan, the football player, the lawyer and the veteran, the Congressman and suburban husband, the champion of Main Street values who brought all of those qualities to the White House.

Once there, he stayed true to form, never believing that he was suddenly wiser and infallible because he drank his morning coffee from a cup with a presidential seal.

He didn’t seek the office. And yet, as he told his friend, the late, great journalist Hugh Sidey, he was not frightened of the task before him.

We could identify with him — all of us — for so many reasons. Among them, we were all trapped in what passed for style in the 70’s with a wardrobe with lapels out to here, white belts, plaid jackets and trousers so patterned that they would give you a migraine. The rest of us have been able to destroy most of the evidence of our fashion meltdown, but presidents are not so lucky. Those David Kennerly photographs are reminders of his endearing qualities, but some of those jackets — I think that they’re eligible for a presidential pardon or at least a digital touchup.

As a journalist, I was especially grateful for his appreciation of our role, even when we challenged his policies and taxed his patience with our constant presence and persistence. We could be adversaries but we were never his enemy, and that was a welcome change in status from his predecessor’s time.

To be a member of the Gerald Ford White House press corps brought other benefits as well as we documented a nation and a world in transition, in turmoil. We accompanied him to audiences with the notorious and the merely powerful. We saw Tito, Franco, Sadat, Marcos, Suharto, the shah of Iran, the emperor of Japan, China with Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping all at once, what was then the Soviet Union and Vladivostock with Leonid Brezhnev, and Helsinki at one of the most remarkable gatherings of leaders in the 20th century.

There were other advantages to being a member of his press corps that we didn’t advertise quite as widely. We went to Vail at Christmas and Palm Springs at Easter time with our families. Now cynics might argue that contributed to our affection for him. That is not a premise that I wish to challenge.

One of our colleagues, Jim Naughton of The New York Times, personified the spirit that existed in the relationship. He bought from a San Diego radio station promoter a large mock chicken head that had attracted the president’s attention at a G.O.P. rally. And then, giddy from 20-hour days and an endless repetition of the same campaign speech, Naughton decided to wear that chicken head to a Ford news conference in Oregon with the enthusiastic encouragement of the president and his chief of staff, Dick Cheney.

In the next news cycle, the chicken head was a bigger story than the president. And no one was more pleased than the man that we honor here today in this august ceremony.

When the president called me last year and asked me if I would participate in these services, I think he wanted to be sure that the White House press corps was represented. The writers, correspondents and producers, the cameramen, photographers, the technicians and the chicken.

He also brought something else to the White House, of course. He brought the humanity that comes with a family that seemed to be living right next door. He was every parent when he said my children have spoken for themselves since they were old enough to speak — and not always with my approval. I expect that to continue in the future.

And was there a more supportive husband in America than when his beloved Betty began to speak out on issues that were not politically correct at the time. Together, they put on the front pages and in the leads of the evening newscasts the issues that had been underplayed in America for far too long.

My colleague Bob Schieffer called him the nicest man he ever met in politics. To that I would only add the most underestimated.

In many ways I believe football was a metaphor for his life in politics and after. He played in the middle of the line. He was a center, a position that seldom receives much praise. But he had his hands on the ball for every play and no play could start without him. And when the game was over and others received the credit, he didn’t whine or whimper.

But then he came from a generation accustomed to difficult missions, shaped by the sacrifices and the depravations of the Great Depression, a generation that gave up its innocence and youth to then win a great war and save the world. And when that generation came home from war, they were mature beyond their years and eager to make the world they had saved a better place. They re-enlisted as citizens and set out to serve their country in new ways, with political differences but always with the common goal of doing what’s best for the nation and all the people.

When he entered the Oval Office, by fate not by design, Citizen Ford knew that he was not perfect, just as he knew he was not perfect when he left. But what president ever was?

But he was prepared because he had served his country every day of his adult life and he left the Oval Office a much better place. The personal rewards of his citizenship and his presidency were far richer than he had anticipated in every sense of the phrase.

But the greatest rewards of Jerry Ford’s time were reserved for his fellow Americans and the nation he loved.

Farewell, Mr. President. Thank you, Citizen Ford.

Historian Richard Norton Smith's Eulogy for President Ford

Historian Richard Norton Smith

Grace Episcopal Church

Grand Rapids, Michigan

January 3, 2007

No one ever called Gerald Ford an imperial president. Perhaps that was because no figure in memory was so immune to Washington’s besetting disease of self-importance. Case in point: Seven years have passed since Marty Allen and I found ourselves in the Fords’ living room at Rancho Mirage, for what, in any other living room, would have been the most uncomfortable of conversations – a discussion of funeral planning. That it wasn’t the least bit uncomfortable was due entirely to the Fords’ sensitivity, their utter lack of pretense, and, not least of all, a robust sense of humor reminiscent of that other plainspoken Midwesterner, Harry Truman.

After a lengthy review of his plans, the President was called away to the phone. A few minutes later he returned, with a grin on his face and a question on his lips.

“Well,” he asked in a booming voice, “have you got me resurrected yet?”

All this week Americans, many of them too young to recall the strident summer of 1974, have watched grainy images of an East Room inaugural. We have listened once more to the words that calmed a nation at war with itself. Thrust into a place to which he had never aspired, Gerald Ford resolved to make his presidency a time of healing, even as he drew out the poisons released by Vietnam and Watergate.

So he didn’t only pardon Richard Nixon; he opened the door for thousands of Vietnam draft evaders to find their way home. In his first days there, he welcomed to the Oval Office the Congressional Black Caucus, leaders of organized labor, and others who for too long had felt excluded from America’s House. Hail to the Chief gave way to the University of Michigan Fight Song. The Justice Department was purged of politics, the CIA reigned in.

Thirty years later we acknowledge with pride what then we only dimly perceived - Gerald Ford gave us back our government. But there was much more to the Ford presidency than ending our long national nightmare. With the passage of time and the cooling of passions, historians have begun to recast his 895 days in office, not as a coda but as a curtain raiser. He was, after all, the first president to pursue economic deregulation or propose a comprehensive energy policy.

His critics boxed the ideological compass. The Left called him intransigent for his refusal to trade away the cruise missile, a weapons system then in development, in order to obtain an arms agreement with the Soviet Union. The Right denounced him for signing the Helsinki Accords, which allegedly conceded eastern Europe to the men in Moscow.

Today we know better. It is hard to imagine America’s military arsenal without the cruise missile. And thirty years on, Helsinki has come to be seen as an important victory in the age-old struggle for human rights, on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

By 1974 it was rare to hear a president laugh; so it was all the more reassuring to hear our new president laugh at himself. Once, after an enthusiastic campaign crowd cheered him to the rafters, a beaming chief executive asked a group of accompanying reporters what they thought of his speech. There ensued a few moments of awkward silence, finally broken by the president’s frank assessment: “Not worth a damn, was it?”

Gerald Ford could be a surprising man.

I discovered this for myself thirty years ago, when called on to introduce the then Vice-President of the United States to the Harvard Republican Club. It was an eye opening event for everyone concerned. We were surprised that Richard Nixon’s vice president would venture so deep into hostile territory. No doubt he was surprised that there were enough Republicans at Harvard to form a club.

While chatting off-stage, I couldn’t resist showing our guest a less than flattering caricature that had been plastered all over campus by Students for a Democratic Society – the same organization that was, even then, noisily demonstrating its displeasure outside the Harvard Club. Reflecting the tenor of the time, the poster depicted Vice President Ford as a grinning puppet impaled on the arm of a sinister looking Richard Nixon.

Most politicians would have blanched at the sight. Gerald Ford chuckled. Then he asked me if he could have a copy to display in his office.

Years later, trustees of his presidential library foundation were debating whether to obtain for permanent exhibit the staircase that had once stood atop the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, and which had served as a final means of escape for thousands of Americans and South Vietnamese in April, 1975. To those who asked, why on earth remind people of that humiliating experience, President Ford had a ready answer. “It’s part of our history,” he said.

And then he revealed a vision few expected from this laconic Midwesterner. To the President that staircase symbolized, no less than the slab of Berlin Wall already on display, a desire for freedom as old as humanity itself. He knew whereof he spoke – for when Congress tried to pull up the ladder and slam shut the doors to Vietnamese refugees, it was President Ford who went to the country reminding us of our history and of our moral obligation to shelter the oppressed. Eventually he was able to rescue and resettle 130,000 of the war’s most innocent victims.

On a bittersweet day in 2000 he came home to Grand Rapids, where he joined hundreds of members of the Vietnamese community in remembering a painful past, and in renewing a shared commitment to uphold freedom against those who would put the soul itself in bondage.

Gerald Ford could be a surprising man.

As part of the Millennium celebrations, Time Magazine invited prominent Americans to identify the pre-eminent figure of the twentieth century, along with a backup selection in case their first choice had already been taken. I fully expected President Ford to nominate a Winston Churchill or Dwight Eisenhower. He did nothing of the kind. Without hesitation he declared the greatest man of the century to be Mahatma Gandhi. The second greatest, in his opinion, was Anwar Sadat.

Think of it: two peacemakers from the Third World, men of color, defiers of the colonial West, each martyred for his convictions.

By then I shouldn’t have been surprised. To most of us, advancing age means a narrowing of sympathies. Our attitudes harden along with our arteries. But not Gerald Ford. His friendship with President Carter, unlikely as it may seem in this era of scorched earth partisanship, reveals much about a leader who never confused moderation with weakness, nor compromise with surrender, and who in his own estimation had adversaries, but not enemies.

For sixty years he was a patriot before he was a partisan. If he never mastered the art of the soundbite, it is equally true that he never turned to a focus group to locate his convictions. He was better at statesmanship than salesmanship. To be sure, Dorothy Ford’s son put his faith in God before government. But precisely because he revered the individual as a creature of God, he respected individual choices.

In contending for the greatest of all freedoms – the freedom to be oneself – he did not hesitate to dissent from party orthodoxy. This, too, should have come as no surprise - for he had first entered politics as a rebel with a cause, a young veteran of World War II who was unafraid to take on the entrenched isolationism of his own party’s establishment.

Through it all he drew strength and inspiration from the family he loved, like his country, with an old-fashioned intensity. He cherished beyond words Mike, Jack, Steve and Susan; his extended family; his brother Dick, his beloved grandchildren and great–grandchildren. And how much they gave back to him, especially in these last few years, when the roar of the crowd yielded to the infant’s laughter and the mellow kinship of Indian summer.

He often said that his was a life richly blessed. The greatest of his blessings was to share a journey of 58 years with a woman whose courage and candor matched his own. The President famously observed that he was a Ford, not a Lincoln. But in at least one respect he was wrong. For his devotion to Betty Bloomer, of Grand Rapids, recalls nothing so much as the sentiment engraved on a plain wedding band presented by a rising prairie politician to his bride, Miss Mary Todd. “Love Is Eternal” it read.

And so it is. He was so proud of you, Mrs. Ford, proud of your bravery and bigheartedness in teaching us all that what some might mistake for personal weakness is but the gateway to spiritual witness, and that no life is beyond redemption. Naturally you were at his side that morning five and a half years ago when the John F. Kennedy Library presented him with its Profiles in Courage Award.

The award was a lantern, an exact replica of the beacon hung in a Boston church steeple to warn American patriots of an advancing British army in April, 1775.

Though it recalled a time of intensely partisan feelings, the ceremony itself was a ritual of healing – the final act of the Ford presidency, and a fitting climax to a life that wed principle to reconciliation. As the least self-dramatizing of men, President Ford used to joke that he was charismatically challenged. Whatever he may have lacked in charisma, he more than made up for in character.

In accepting the Profiles in Courage Award, he expressed the hope that no future president would ever confront the choice that he faced barely one month into his presidency of healing.

But if he did, or should he be presented with an even greater test of national character, said President Ford, “I hope he will remember that the ultimate test of leadership is not the polls you take, but the risks you take. In the short run, some risks prove overwhelming. Political courage can be self-defeating, but the greatest defeat of all would be to live without courage, for that would hardly be living at all.”

And now he has come home, to the place, emotionally, he never left. Not long before he died, the President remarked, “When I wake up at night and can’t sleep, I remember Grand Rapids.” That Grand Rapids returned his affection many times over was unforgettably demonstrated by the tens of thousand who stood in line for hours outside the Museum, braving the cold to make certain that his last night was anything but lonely.

Soon we will take him to his final place of rest, our grief mingled with gratitude for a life that is its own lantern in the steeple. May the glow it casts remind us of a politics that elevates rather than divides; and of a country as honorable as it is powerful.

Sleep well, old friend. We love you very much.

Martin J. Allen' s Welcoming Remarks

Martin J. Allen

Chairman Emeritus Gerald R. Ford Foundation

Gerald R. Ford Museum

Grand Rapids, MI

January 2, 2007

Betty – Mike – Jack – Steve – Susan – Brother Dick, Members of the Ford family, the Ford staff, and Friends of Ford

There is a group here that could be classified as Friends or Family, the U.S. Army Chorus who have been with the Fords for so many of their significant events while in the White House and after. One of the many events that they performed in Grand Rapids was the dedication of this museum. They have adopted the Ford family as the family has adopted the chorus. It is most appropriate that they are here today and for tomorrow’s services.

“Grand Rapids, Michigan – a place from which a man can journey far and never leave.”

These words are taken from Jim Cannon’s book on President Ford entitled Time and Chance. Jim came to Grand Rapids with an understanding of the Midwestern culture, but when he left he had a much better understanding of what shaped President Ford’s values and characteristics developed throughout his formative years. He found a young man whose family values were based on simple but profound Ford rules – “tell the truth, work hard and be at dinner on time.” He abided by the Boy Scout oath-"duty to God and country"-- and achieved the distinguished title of Eagle Scout. He experienced discipline, courage, and competitiveness with respect for opponents as a football player at South High School. Those values would endure throughout his life and evolved characteristics of decency, integrity, civility and goodwill.

“A place from which a man can journey far and never leave” – and journey from Grand Rapids he did…to the University of Michigan, Yale University, the South Pacific during World War II, Alexandria, Virginia, the White House, Colorado, and California…but wherever he journeyed, the values forged in Grand Rapids never left him.

And most important to him-of all of his memories and experiences in Grand Rapids – it was in this city where the great love story of Jerry Ford and Betty Bloomer had its beginning – a beginning that would have no end. The concise, but powerful, words selected by President and Mrs. Ford inscribed at the burial site say it all…“Lives committed to God, Country and Love.”

We have just completed the 25th anniversary of the dedication of this museum. For over 20 years, I have had the privilege – indeed the pleasure- to meet President Ford at these entrance doors whenever he visited his presidential museum. I always greeted him the same way – “welcome home Mr. President” and he always responded – “Marty it’s good to be home.”

Following Governor Granholm’s remarks, the U.S. Army Chorus will sing the beautiful hymn that asks the question in its title – “Shall we gather on the River?” and is answered by the refrain “yes, we’ll gather at the river.”

And so we gather here to conclude President Ford’s final journey from California to Washington, D.C. to the city he never left, Grand Rapids to say…“Welcome Home Mr. President.”

Governor Jennifer M. Granholm

“Welcome Home Ceremony” for President Ford

Gerald R. Ford Museum – Grand Rapids

January 2, 2007

To Mrs. Ford, Michael, Jack, Steven and Susan, friends of the Ford family, President and Mrs.

Carter, and honored guests: On behalf of the state of Michigan, welcome. We are proud and

honored that you are here.

And to President Ford: Welcome home, Mr. President.

Welcome home to the city where you ate dinners with your family on Union Avenue, where you

laughed with your high school football friends, and graduated with honors from Grand Rapids

South High.

Mr. President, welcome home to the state and the city where your mother and your stepfather

baked into your young life some good Midwestern values – hard work, sportsmanship, integrity,

honesty.

Welcome home to the city you returned to after serving your country in the war. Welcome home

to the city where you and Betty were married, at Grace Episcopal Church – Betty in a $50 dress,

and you in muddy shoes.

Welcome home to the district you represented in Congress so well for 25 years, while living on

Crown View Drive. And welcome home to the people you reflected so well when you were in

Washington. You probably saw as the motorcade drove in citizens of Grand Rapids on freeway

overpasses, children holding signs saying “Welcome Home.” We are so proud.

And let me just observe, sir, that a lot has been said about your humility, simplicity, low-key

approach to leading. But we won’t let all that understated-ness fool us – you were incredible. We

all know about being a high school and college football star, but… an Eagle Scout, a war hero, an

honors graduate of the University of Michigan and Yale Law School. In fact, the most delightful

secret about Jerry Ford is that you were a paradoxical gift of remarkable intellect and

achievement, wrapped in plain brown paper.

Mr. President, you embodied the Midwestern spirit illustrated in the three rules you often said

your parents taught you – tell the truth, work hard, and come to dinner on time. I cannot think of

three better rules to live by, whether you are a boy growing up in Grand Rapids or the President

of the United States.

I was listening to the commentators on the news this morning describe the actions yesterday by

Susan and Jack and Michael and Steven as they personally shook the hands of mourners who

came to pay their respects – the commentators described their graciousness and warmth and

accessibility as an example of good Midwestern values. It made me proud. I’m sure that you

were proud too, Mr. President.

We were proud to see the down-to-earth spirit you brought to the White House. We are proud

that we will put you down in our Michigan earth, right here.

Welcome home, Mr. President, to a state proud of your time as not only the nation’s president,

but our president. Michigan’s president.

Mr. President, you said at the rededication of this museum in 1997: “Like a runner nearing the

end of his course, I hand off the baton to those who share my belief in America as a country that

has never become, but is always in the act of becoming. Presidents come and go. But principles

endure, to inspire and animate leaders yet unborn. … That is the mission of every American

patriot. For here the lamp of individual conscience burns bright. By that light, we can all find

our way home.”

Mr. President, we are proud that you have found your way home.

House Speaker Dennis Hastert 's Eulogy for President Ford

House Speaker Dennis Hastert

U.S. Capital Rotunda

Washington, D.C.

December 30, 2006

Mrs. Ford and Members of the Ford Family, Mr. Vice-President, Members of Congress, Distinguished Guests.

I don’t think it is a coincidence that American history seems to be an almost providential narrative – a story about finding the right man at the right time to lead the nation. The Presidency is more than agendas and ideas. It is, at its core, a human institution molded and shaped by the character of the men who have served there. In the summer of 1974, America didn’t need a philosopher king or a warrior prince, an aloof aristocrat or a populist firebrand.

We needed a healer.

We needed a rock.

We needed honesty and candor and courage.

We needed Gerald Ford.

President Ford was one of the few men in history who did not need great events to make him great.

On the football field, in the halls of Congress, and in the Oval Office, there was always something big and solid about him. Big and solid and good.

In this sacred place, the President now Lies in State under the Statue of Freedom. On the way here we paused at the door to the House of Representatives. In that place – the People’s House – where Gerald Ford served for a quarter of a century – he was known simply as “The Gentleman from Michigan.”

And while all members are afforded this courtesy, in the case of Gerald Ford -- “gentleman” – was much more a description of the man himself.

For in a time when turmoil and bitter division were all too common, he stood out as a man of deep civility, quiet thoughtfulness and sound judgment.

Like Abraham Lincoln, another great Midwestern President who confronted a nation divided, Gerald Ford was called upon to bind our country’s wounds. The twin crisis of Vietnam and Watergate had crippled America – sapped our strength – shaken our confidence. With humility and devotion to purpose, Gerald Ford united us once again.

In an era of moral confusion, Gerald Ford confidently lived the virtues of honesty, decency and steadfastness. His example of fairness and fair play, of dignity and grace, brought forth in us our better instincts.

He reminded us who we should be and he helped us to heal.

The traits that Gerald Ford showed us as a Congressional leader -- the ability to listen, the courage to forge compromise in the face of shrill partisanship, and the willingness to make the hard, and sometimes unpopular decisions, served him well as President.

The critics of the day got it wrong, but history is getting it right.

Despite his considerable achievements, the greatness of Gerald Ford lies not in what he did -- but in who he was. He represented the strength of the Middle America that forged him.

He never changed.

Even when power was thrust upon him he remained an “every man” who exemplified all that is good about America.

Mrs. Ford, you were his best friend, his close partner – and, along with his faith, the source of his strength. You and your children knew him as a devoted family man and you loved him for his integrity, his kindness and his humor.

As the leader of our country at a difficult time in our history, it was those qualities that drew a grateful nation to him as well.

We can never thank you enough for sharing him with us.

Just a few feet from here – in the House Chamber – Gerald Ford was sworn in as Vice-President of the United States. It would not be long before he would become our President.

Speaking to the nation after taking the oath as President he concluded by saying:

“I now solemnly reaffirm my promise to uphold the Constitution, to do what is right as God gives me to see the right and to do the very best for America. God helping me, I will not let you down.”

You did right, Mr. President.

You did not let us down.

Well done, good and faithful servant.

God speed Mr. President.